Why Read Beowulf?

4 Reasons You Should Read the Great Anglo-Saxon Classic

It has been called a shadow of shadows, an echo of echoes - this story from our far-distant past. Here is a narrative poem reaching back to a time when the ancestors of the English lived in tribal communities. Though old, Beowulf remains a relevant literary masterpiece.

But why should a reader in our modern era even bother?

Background on Beowulf

In 1700 an Anglo-Saxon librarian named Humphrey Wanley came across a most curious document. In his hands he held a codex with eight unrelated documents. One of these, a vellum manuscript seven hundred years old, told the confusing story of ancient kings and tribes and a legendary hero who fought a dragon. A piece of antiquity had resurrected giving the modern world a myserious glimpse into the forgotten past.Treasured by many, and scorned by many others, the poem became the center of an almost ubiquitous rite of passage: "Why should I read Beowulf"?

While critics abound, it should be said that there are few-to-none actually suggesting we get rid of prized manuscript. Even a shopping list that was one thousand years old would have museum-worthy value - how much more a 3000 line poem about humanity’s family tree. The critique could perhaps more accurately be addressed as a question: “Of all the classics out there, why should my kid be assigned to read Beowulf?” Or even better, “Of all the books on the library shelf, why should I pick up Beowulf and re-read it?”

The Antithesis

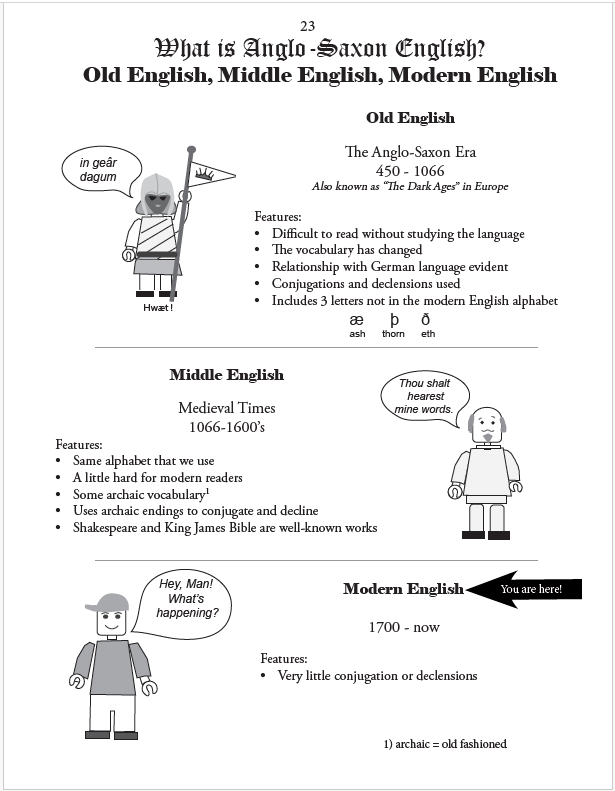

Critics: Beowulf is too Hard to Read

Beowulf, it’s critics say, is hard to read and not worth the effort. And an honest answer to those critics must agree that it is, indeed, hard to read. This becomes obvious when one opens the cover and encounters these first words: “Hwäet! we Gâr-Dena in geâr-dagum þeód-cyninga þrym gefrunon.”Old English, it turns out, has undergone a few changes in the last thousand years making it a trifle hard to understand. Shakespeare, for instance, came five hundred years later making him practically modern in comparison.

While the good news may be that there are dozens upon dozens of modern translations, the bad news is that those translations aren’t entirely satisfactory. Translators face a dilemma that ends up a problem for us, the readers. If the translator translates word for word, finding the best modern equivalent and placing it on paper, we can follow the original - at least somewhat. But it’s almost as smooth to read as the sentences of a drunk person writing Pig Latin.

Some translators abandon the word-for-word approach and instead try to keep the poetic form. It’s quite likely that as you stumbled over the words above you noticed it was written as a poem - even though you probably slaughtered the poem so badly the original poet would have been ashamed to listen to it. The poetic approach does allow us to enjoy the lofty inspiration - if we have any idea what it’s talking about.

Then there is the story-teller’s approach: tell the story like a story. Beowulf can even be made into an action movie. It’s been done. But quite honestly, something marvelous in the original poem is lost when we modernize it too much.

And therein is much of the difficulty: Beowulf is a poem and modern consumers of literature like their stories handed to them in the form of a novel. It’s what we are used to. Once one finally accepts that the story is served poetic style, a new hurdle arises. We like our poems to rhyme; they liked theirs to alliterate. It takes a little getting used to: all those funny phrases and keen kennings that allowed alliteration to abound. Sentences begin to make more sense once the reader realizes that they begin and end in the middle of the line - wrecking havoc with our expected word order.

For the open-minded reader that clears those hurdles, they are finally rewarded - with a bunch of allusions to historical characters they never knew or cared existed. The author really thinks we already know who Hrothgar and Hreardred and Hrothulf are (and can keep them all straight.) Many readers just skip those allusions and then, sadly, miss the whole poetic point.

But those brave souls who stumble through to the end gain the advantage of having read a story about a strong guy who fights a troll, its mother, and a dragon.

That’s it? Is this Classic Literature 101 or Marvel Comics?

So yes, Beowulf-proponents are forced to acknowedge that this old poem is hard to read and presents the modern reader with a few challenges. But missing from the critics negative assessment is the simple truth that great translations with accompanying footnotes abound. It’s a long poem; but a short story. Surely one can take a few extra seconds to read an explanation or look at a chart. Because attentive readers are rewarded with a timeless masterpiece that reflects culture, civilization, ethics, and the ancient questions of life and death.

#1 - Cultural Literacy

The first reason for reading Beowulf is the simplest and, perhaps, the least important.Beowulf is a cultural icon. Whether an individual has the inspirations of a classicist who doesn’t want to be ignorant of the works of Shakespeare, Milton, and other greats, or a popularist who yearns to know the latest action movie and video game, Beowulf tops the list.

Tolkien fans in particular are in for a treat. One cannot accuse Tolkien of plagarising from Beowulf; he loudly and proudly proclaims it himself. Indeed, the ancient text becomes a playing field for a Lord-of-the-Rings-scavenger hunt, for any who wish to play.

Disney fan or fairy-tale fanatic? While none can ascertain that Beowulf is the direct ancestor of all of these, it is accurate to say that it is in Beowulf’s genre that all such stories descended. Beowulf is the oldest in it’s class - the great-granddad of folktales - for English readers anyway.

Traveling minstrels and their transmission of oral tales are familiar to us. One of the most famous of the oral traditions is Robin Hood, which includes a traveling minstrel. Beowulf is not only older, by about seven hundred years, it is our first working specimen of that category.

Literary analysis is a foundation of cultural literacy. Beowulf, one could argue, demonstrates the formation of the elements of literature in their current form. Foreshadowing, flashbacks, exaggeration and understatement, humor, rising action, and mise en abyme are some of the elements we see for the first time in English literature.

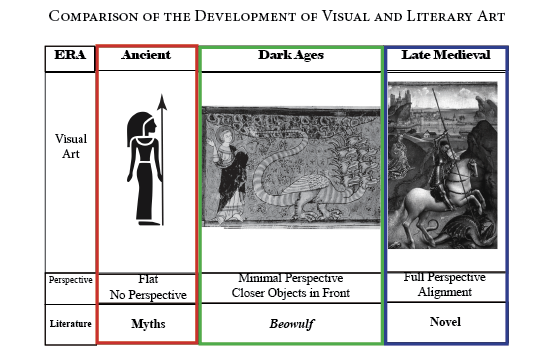

Meanwhile, point of view and transitions are still in the rough. A comparison to the visual art of perspective helps make this point.

But lovers of good literature get to witness one stage in the emergence of our modern novel. Readers gain cultural literacy by reading Beowulf, becoming familiar with a well-known icon and witnessing the transition of literature into its current form.

#2 - Roots of Civilization

Beyond literary skills, a second major reason for reading Beowulf is that it reflects society’s historical and cultural roots. Readers gain an understanding of our political, geographic, cultural, religious, and linguistic history.Obviously, it’s historical. Beowulf lists the royal dynasties of the sixth-century, northern Teutonic tribes. For any historian (or middle schooler) hankering to fill in the gaps of the Geats, Hethobards and other royal families long-forgotten, the discovery of Beowulf was invaluable.

The poem’s genealogies have been put under historians’ microsope, and have stood up to their scrutiny. For just one example, other historical sources record that King Hrothulf killed Hrethric and was later killed by Heoroweard. Only in Beowulf do we learn that these were all cousins, grandsons of Healfdene, obviously competing for the throne and with some familial baggage to boot.

But it just so happens, there are better reasons for you to read the poem than the fact that it lists the siblings and cousins of kings you never knew existed.

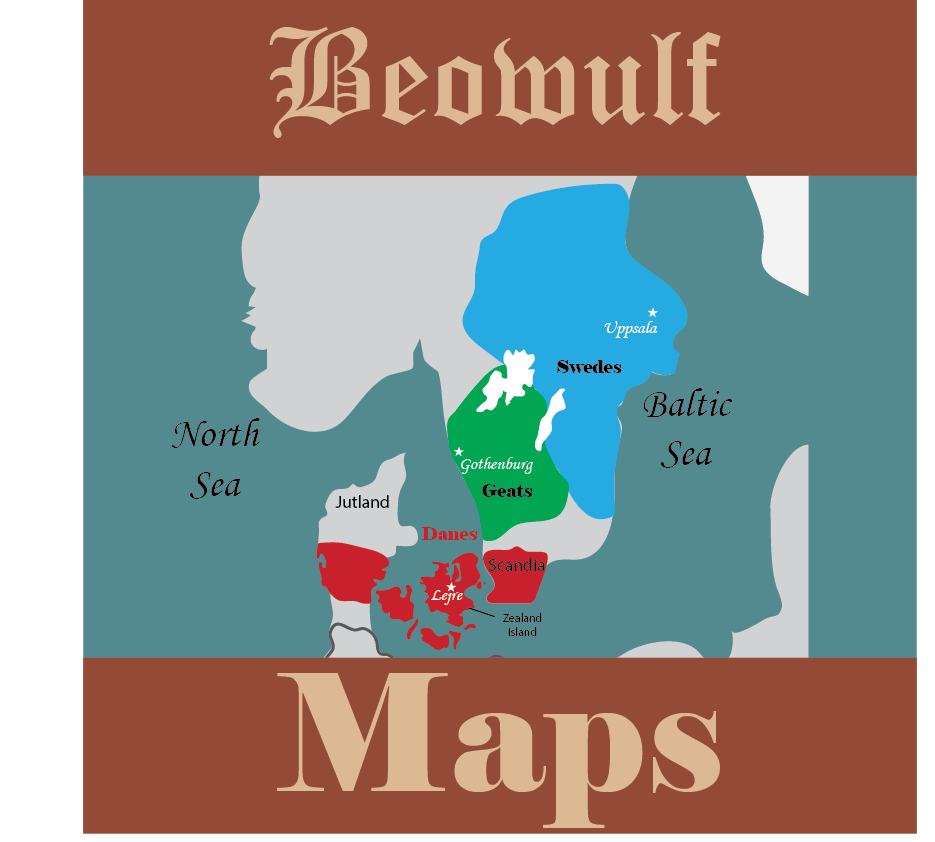

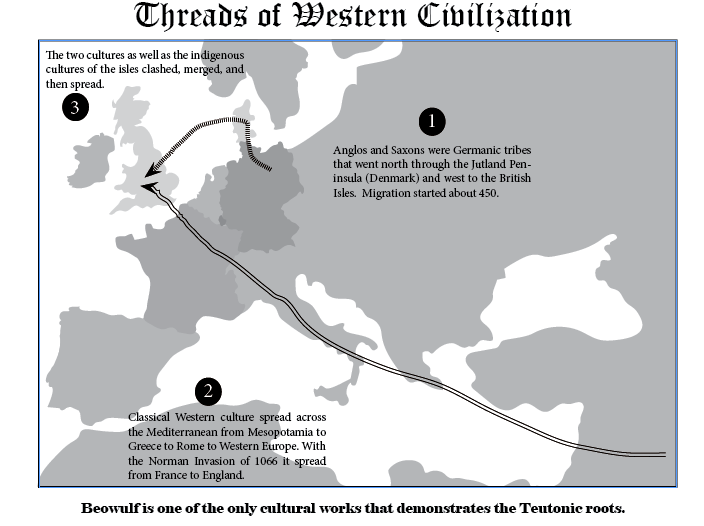

We tend to think of our historical roots as advancing from Mesopotamia to Greece to Rome to Western Europe to the British Isles and then across the Great Pond. “Not so,” Beowulf scholars inform us. The English are the descendants of the pagan Germanic tribes that pushed northward through Denmark then sailed west to land on the British Isles after the Romans had deserted it. (See map below.) Where, other than Beowulf, do students ever come in contact with that part of history?

But the value of Beowulf is not simply learning about the cultural practices contemporary with the poem. It’s about change in culture. Beowulf provides an amazing snap-shot in a singularly significant point of time. That is the time when the English (as well as other Europeans) transitioned from a society of clans/tribes, to a Medieval society with specialization of labor. A millennium later they would transition from Medieval to modern (more or less) and the artistic products of that later transition abound. Beowulf is our only literary point-of-contact with that earlier transition - from a tribal to a labor-specialized society.

This aspect of cultural change makes Beowulf significant for both European and non-European descendants. While Europeans can point to the early Middle Ages as the time of transition away from tribal communities, other cultures made that transition at a different time, different location, and for different reasons. Nonetheless, Beowulf cuts across the ethnic divide - for his story (monsters included) transcends ethnicity. It is the old story of good versus evil, except it was re-told generations later when the concept of good had changed.

For equally significant as the cultural change as they transitioned away from tribal communities, is the religious transition that occured. Modern readers are often surprised to find references to God and to paganism side by side in Beowulf. In 600 A.D. Christianity reached the British shores, at least for the Anglo-Saxon population. (Some of the older indigenous tribes, like the Celts, had embraced it earlier.) Beowulf’s snap-shot-in-time portrays the author wrestling with the two largely-incompatible belief systems. This provides a unique example of reinterpreting their forefathers' acts through an entirely new lens.

That the author was a Christian has never been doubted, but scholars have long debated the significance of his beliefs. Was he a churchman, a minstrel, or both? Why, if he was a Christian, did he not mention Christ or the New Testament? Was he writing as a first generation believer, or as someone who grew up with Christianity, or as someone who was merely reflecting the beliefs of a patron?

Considering that the author’s identify is unknown to us, it is difficult to determine anything about his faith except what he actually wrote in the poem. And what he wrote is that God is good and the devil is bad - a rather broad perspective. But whoever he was, light-weight theologian he has been accused of being, it should be noted that he addressed a pertinent cultural and theological question still asked by those in and out of the church today: can those who died without the gospel come into Christ’s kingdom? Significant and gutsy question for a theological light-weight!

In England, and elsewhere, widespread literacy followed Christianity. Even commoners learned to read. Not only did the author draw on multiple sources in the poem’s development including pagan folklore, Biblical accounts, historical narratives, Greek and Roman classics, it is apparent that his audience was also familiar with these sources. (It’s the current reader, not the Anglo-Saxon who needs the footnotes to follow the historical trail.) Indeed the modernists tendency to look down on the education of the Anglo-Saxon citizens is challenged by reading Beowulf.

A literate Christian who emerged from a non-literate, pagan tribal background reflected on both societies in his poem. Moreover he conducted that assessment through one of their old heroic tales. His conclusion - that endless war is bad but bravery and sacrifice for others is good - remains universal.

#3 - Morality and Ethics

Good vs Evil

The third reason Beowulf remains relevant for modern readers is the same as the reason for literature in general: the search for good in the midst of bad. The character of Beowulf is a model of morality - primarily as a positive model but, in the end, also a negative model.Beowulf can be an example to all: the original ugly duckling who achieved world-wide fame for strength, nobility, and kindness. It’s not until late in the tale we are told he was discounted by everyone as a child growing up in his maternal grandfather’s court. The author himself doesn’t bother to give him a name until several sections after he is first introduced. Nonetheless, in the first night in Hrothgar’s court we are introduced to his wit, gracious words, and uncanny strength.

In spite of his lack luster start, Beowulf is the epitome of nobility and bravery, putting himself in danger to save others. But as one conflict after another emerges, the author weaves the subtle question: what are all these fights for? The lives of women, in particular, are ruined as they are used as peace-weavers in a near-impossible task of preventing military conflict in a society that thrived on military conflict.

Endless wars for revenge and glory are fruitless. But not all fighting is bad. The eleven warriors who abandoned their king caused the downfall of the Geats. Sometimes one must fight, particularly when the defenseless need defending. The bandit, the suicide bomber, the crooked politican - maybe even the migrating python (since there haven’t been a lot of sightings of fire-breathing dragons in the last few decades) - all are times when the noble are called on to act. Be honorable! Be brave! But don’t be stupid. Risk your own life and the life of your people just so you can get glory for fighting a dragon solo?

Wiglaf was right; Beowulf was wrong. He had ignored the council of Hrothgar to forsake pride and it killed him.

Pride goes before a fall, the good book says. Turns out that Old English poetry and Old Testament theology really do have some relevant ideas for the average man-on-the-street.

#4 - Facing the Inevitable

Literature allows us to explore humanity’s issues by proxy. Death is one of the themes of the poem. Beowulf never held back from doing good because he faced danger or death which, by the way, he faced pretty much all the time.Death has been with us for a long time, it turns out, and people don’t like it much. They are afraid of it, by and large - even more than they are afraid of spiders and snakes. Of course, everyone has different fears, rational and irrational, and many of them are related to death and dying. But if you poll your friends and neighbors you will find 999 times in 1000 that they all have one thing in common: they aren’t afraid of dragons.

Fire-breathing dragons exhale behind a wall of fiction. We recognize that they are scary but we know they can’t jump their own fictitious wall. Add one thousand miles and one thousand years and we can, any of us, read Beowulf’s death without any genuine fear for our own safety. It’s a benign way for us to face what we all will experience eventually anyway.

Considering that Beowulf was a story to be performed by a minstrel in a mead hall, and those mead halls were the gathering place of warriors ready to do battle for their lords, it is reasonable to think that motivating men to face death bravely may have been one of the author’s goals.

And it is obvious that the author, whoever he was, was up-close and personal with the bedside experience of a loved one’s death: the numbness, the solicitation, the plea, the gentle care, obeying the last commands, the lonely vigil, the burst of anger. And finally...the decisions. Even in mind-numbing grief while the body is still warm decisions must be made.

The narrative of Beowulf’s death is unparalleled. Even from the distance of a thousand years, a foreign culture, and a fictitious dragon, the final scene is both life-like and dream-like.

In the end, all must die. Since we, like Beowulf, are going to die anyway, die doing what is right. Beowulf was not worried about how long he lived, but how he lived. None can live as freely and as boldy as those who shun the fear of the inevitable.

Beowulf is like a mirror in a mirror whose back-and-forth reflection of itself is endless. His father’s tribe is no more; his mother’s tribe will meet the same fate; the tribe that buried the dragon-treasure ceased to exist long ago. In that endless reflection perhaps the author saw the demise of his own society ahead. Indeed the Norman Invasion that ended Anglo-Saxon England was only years away from the time our only copy of the poem was transcribed.

For all things die: monsters, heroes, and civilizations.

Get the Beowulf Unit Study

Unlock the action plot, history, and debates of the ancient tale.

Available in Paperback OR Printable Download

253 pages

(Includes Student Pages, Teacher Key, References, Maps, Charts and More!)

Print It Now

![]()

$5.99 Your link to print will last for five days.

Ready-in-a-minute lesson plans can be used with any translation.

Easy-to-read summary for each section.

Softcover Edition - Mailed to You

The same pages are in the softcover book and the printable file. Keep your papers bound together and use this book for years to come. It will be your go-to-guide for all things Beowulf!

![]()

17.95 Soft Cover Manual

Mailed to You

Beowulf Pages

Check here for all things Beowulf.

About Our Site

Hands-On Learning