Paul Revere Critique

This critique of Paul Revere's significance is part of the Paul Revere Unit Study for educators. See below for more information.The Myth of the Myth

It is highly fashionable in some circles to critique and “debunk” well-known characters or events from history. Therefore one can readily find articles down-playing either Paul Revere, the rider, or Longfellow, the poet who wrote the now-famous account of Revere’s legendary ride. Some have gone so far as to claim that Revere’s fame was caused by Longfellow’s poem which is little more than a myth.Adding insult to injury, some critics go further, insisting that Longfellow’s Midnight Ride of Paul Revere isn’t even good poetry. This begs the question of how a bad poem should cause a supposed minor character from the mists of history to become one of the most recognized names in American history.

If we should accept the modern critics debunking of either Revere’s actions or Longfellow’s poem, the educators in our midst need to ask another question: should the next generation even bother reading the poem or learning about Revere? Hence the title of this article: The Myth of the Myth; for neither Revere’s ride nor Longfellow’s poem are myths. The midnight ride alerting the militia is a historical fact, and the poem is, well, a poem. Longfellow took some poetic license. Poets do that. He wasn’t writing a history text.

Did Longfellow’s poem make Revere famous at the expense of William Dawes or Samuel Prescott? No. In 1861 when the poem was published, 86 years after the event, Paul Revere was already famous. He was one of Boston’s most acclaimed citizens, a celebrated Son of Liberty, a military officer in the Revolution (not a particularly successful one, but still loyal to the core) and an eminent enterpreneur. A simple internet search will demonstrate the difference in fame by listing how much more information is available on Revere than the others since the generation following him recognized the value in preserving it. Before the poem was written, almost all of the homes in Revere’s Bostonian neighborhood were torn down, but his was preserved due to his legacy.

More evidence of Revere’s notoriety came to light in 2014, when a time capsule from the cornerstone of the Massachusettes State House in Boston was unearthed and opened. A copper box with numerous artifacts had been buried on the twentieth anniversary of the Revolution in July 1795 in a ceremony by Samuel Adams and Paul Revere. Adams apparently didn’t get the memo that stated Revere was an insignificant character only made famous by a poem written in 1861.

Longfellow chose to make Revere the character of his poem because he was already famous for it, not the other way around. Having said that, it should also be noted that Longfellow’s literary endeavor is itself highly acclaimed and is one of the most famous poems in the English language. Therefore, it is not a stretch to say Longfellow probably promoted him from an American Revolutionary hero to a household word around the English-speaking world. And many Americans who would be hard-pressed to list the order of events of the Revolution can readily recite, “on the eighteenth of April in 75.”

“But Longfellow took out the contributions of Dawes, Prescott, and others,” some critics might argue. That he did - and for good reason. Without degrading the contribution of the others, it should be noted that Revere had the more urgent message and the more important role. Dawes left Boston by land at about nine pm, Revere rowed across the Charles River about eleven pm.

Read a detailed chronology of the Timeline of Paul Revere

Both men wanted to warn Concord about the British plan to seize munitions stored there, but the two men planned different routes to ensure at least one would make it. But something else happened between the times of their separate departures. The British started rowing for the opposite shore, the move was on, urgency was needed. Dawe’s message was, “The British Redcoats will be coming.” Revere’s message was, “They are on their way and following right behind me.” Note that Revere got to Lexington ahead of Dawes even though he left two hours later and had to contend with passing the Somerset quietly and finding his contact and horse once he reached Charlestown. It was he who recklessly raced the dark roads knowing the Redcoats to be on the march. (Thankfully for Revere and all the militia, the British had several delays in their water crossing or things might have turned out differently.)

One of the fallacies of the “Myth of the Lone Rider” criticism is just that. A lone rider could not knock at 3000 doors to get those 3000 minutemen to Concord in a three hour ride. That would be one thousand doors an hour or about three farms every minute. The entire point missed by some modern critics is that the Sons of Liberty HAD established an effective network and when the time was ripe, the fuse was lit. “And the spark struck out by that steed in his flight, kindled the land into flame with its heat.”

A lone man could not have done that; it was the Sons of Liberty and others that did it as a group. Revere and Dawes themselves were working under the authority of another. We know from history that unnamed leader was Dr. Joseph Warren, president of the Massachusetts Provincial Congress, and close friend of Revere’s who gave the orders. Longfellow did not see fit to include in his poem such details as who gave Revere the information, what William Dawes was doing and when, or even the fact that Revere had started out on the same route several times prior to April 18 on the same mission but terminated it as nothing yet was happening. The poem is long enough as it is.

The duties of literary analysis require that three historical inaccuracies in our poem pounced on by critics should be examined in the context of a poetic reconstruct of a historical event. First is the accusation that Longfellow got the “one if by land, two if by sea” narrative wrong. We do know that Revere was a friend of Robert Newman and made previous arrangements with him regarding how many lights to hang in the tower (one if by land, and two if by sea IS correct.) Newman was sexton (janitor, bell-ringer, graveyard manager, etc.) of the North Church and his mother rented some of their rooms to British officers. Officers in the house, keys to the belfy; what a great set up for this gig! The entire rig was pre-arranged several days before the big day. The lights would let the Sons of Liberty on the Charlestown shore know what to expect, since the Charlestown folks were in on it too. Someone over there had a borrowed horse ready for Revere. And if he hadn’t successfully crept past the Somerset, the patriots of Charlestown would have had to take Revere’s place.

Now, it just so happened that when the hot scoop came on the night of the 18th, Revere made a detour to let Newman know the latest intelligence before he got in a rowboat with two others. Newman himself was part of a threesome that carried out that part of the scheme that night and was, incidentally, arrested for it the next day. So yes, Longfellow did leave out lots of fascinating tidbits, even neglecting to name Newman (though he does have him loitering for quite a while in the belfry and looking out over the cemetery he maintained for an inexplicable 21 lines. Longfellow must have been in a somber mood and stuck on those verses on a chilly, foggy night in 1860, I’m thinking.)

So it is true that Longfellow left out lots of details. It is interesting that there were three patriot riders, three undercover agents at the bell-tower, and three conveyers rowing across the Charles River; but only one gets mentioned in each case. Now granted, lines 56-72 do make it sound like Revere lingered on the shore waiting for Newman to get the intel to him. I don’t doubt that Revere did linger to search for the lantern light in the belfry. After all, the intel MIGHT have changed, and Revere was counting on Newman’s lanterns as part of the bigger strategy.

The next inaccuracy is the chronological hours listed in the poem. Even a child can perceive that the times mentioned are rough approximations: “It was twelve by the village clock when he crossed the bridge into Medford town... It was one by the village clock when he galloped into Lexington...It was two by the village clock when he came to the bridge in Concord town.” I’m hoping that even the most obsessive historian will recognize the use of a poetic device in the repetition here and forgive Longfellow’s rough and not very believable chronology. According to Revere’s account, it was actually 11:30 when he got to Medford, and he left Lexington a little after 12:30.

And Concord? Well, that’s definitely another historical faux pas. Revere didn’t actually make it to Concord because he got arrested. Minor detail omitted in the poem. Actually, there are a number of such minor details omitted between lines 109 and 110. These include such trivial matters as warning John Hancock and Samuel Adams; meeting up with Prescott and Dawes; getting arrested, released, and walking back to Lexington; transporting secret documents a few blocks away from the Lexington Green and hearing the famed “shot heard around the world;” as well as the entire Battle of Lexington and the Battle of Concord and the start of the Revolutionary War.

Longfellow skips over all that. In a poetic sense, one might say Revere made it to Concord because Preston got there on his behalf, the only one of the three riders to make it. It was no insigificant feat because Preston warned Concord, continued on to Acton, and it was the guard from Acton that played a major role repulsing the British at the famed North Bridge. The point of the whole poem was that Revere successfully got the word out and therefore 3000 militia were on hand in Concord to show the world that America was ready to fight for liberty.

Indeed from the foreshadowing lines 108-109: “Who that day would be lying dead, pierced by a British musket ball” to the allusionary lines 110-111 “You know the rest. In the books you have read, how the British Regulars fired and fled,” the poet is assuming that we, the readers, actually know our history. He conjectures that we know about Newman and Warren and Dawes and Prescott and Hancock and Adams. He presumes that we know the midnight ride preceded the Shot Heard Around the World and the Battles of Lexington and Concord. He expects we know that Revere was arrested by the British (after all a monument still marks the spot.) There’s no shame in having a British patrol threaten to blow your brains out for doing your duty to warn your countrymen. Particularly when you have already set the fire that can’t be stamped out.

Perhaps Henry Wadsworth Longfellow would even conjencture that we might know that his very own grandfather, Brigadier General Peleg Wadsworth, would bring charges against Lt. Colonel Paul Revere for disobeying his orders in the Penobscot Expedition - a military disaster that destroyed the American fleet in the summer of 1779. Disgraced by charges of cowardice, neglect of duty, and insubordination, Revere pushed for a court martial which eventually cleared his name of all charges, including those brought by General Wadsworth. That catastrophe was not Revere’s fault and so time, history, and the court martial erased the guilt placed on him.

Longfellow was not writing a history text. It is not an invalid question to ask if those three named inaccuracies (who the lantern warned, times of the arrival in the towns, Revere’s failure to reach Concord) were caused by poetic license or a simple mistake. With a few clicks of a mouse you and I can read Revere’s own account (though the modern transposition is a great help even with Revere’s artistic lettering.) Longfellow didn’t have the wealth of information right at his fingertips. Perhaps he didn’t know Revere was stopped a short distance from Concord, or perhaps he let Prescott symbolically take Revere’s place. He was honoring a brave man for a brave deed and explaining the symbolic value of that act: “In the hour of darkness and peril and need, the people will waken and listen to hear.” One committed person can move a nation, not if that one stands alone but if he or she sounds an alarm that others heed.

It is laughable that some - in fact many- call this a myth. Longfellow came from an age when it was expected that the masses knew their basic history and could understand a poem giving homage to that history. In fact, the poem’s larger context is a grandfatherly inn keeper telling tales in the public dining room. It’s theme is America’s past; it’s purpose is to preserve patriotism and a love of liberty.

Shall we agree with the critics that this is romantic symbolism not worthy of poetic merit? Since some literary critics thumb their nose at the ability of the common population to recognize quality verse, the fact that it sold out the first day it was published would be of no consequence to them. (Seriously, not many poetry books can claim that honor.) Ask them how many reprints have been demanded of THEIR poems. The answer will likely be silence.

There are many qualities of this poem that do achieve literary excellence. All who have tried their hand at writing verse recognize that it is harder than getting a set number of syllables per line that rhyme at the end of the line. The rhythm and staccato or smoothness of the sounds is important. Throughout the poem we have an unparallelled rhythm of a galloping horse. And those who like to analyze the aabb of poetic rhymes will be in for a real treat:

- AABBA

- CDCDEE

- FFFGG

- HHGIIJJ etc.

Its the current trend - calling all things noble a myth. That, we might say, is the myth of our time. Perhaps Longfellow’s extraordinary skill at weaving stories through verse still plays a role for our era with its belief that goodness is gone and liberty is a lie.

"A cry of defiance and not of fear, a voice in the darkness, a knock at the door, and a word that shall echo forevermore."

Teaching the Paul Revere Unit Study

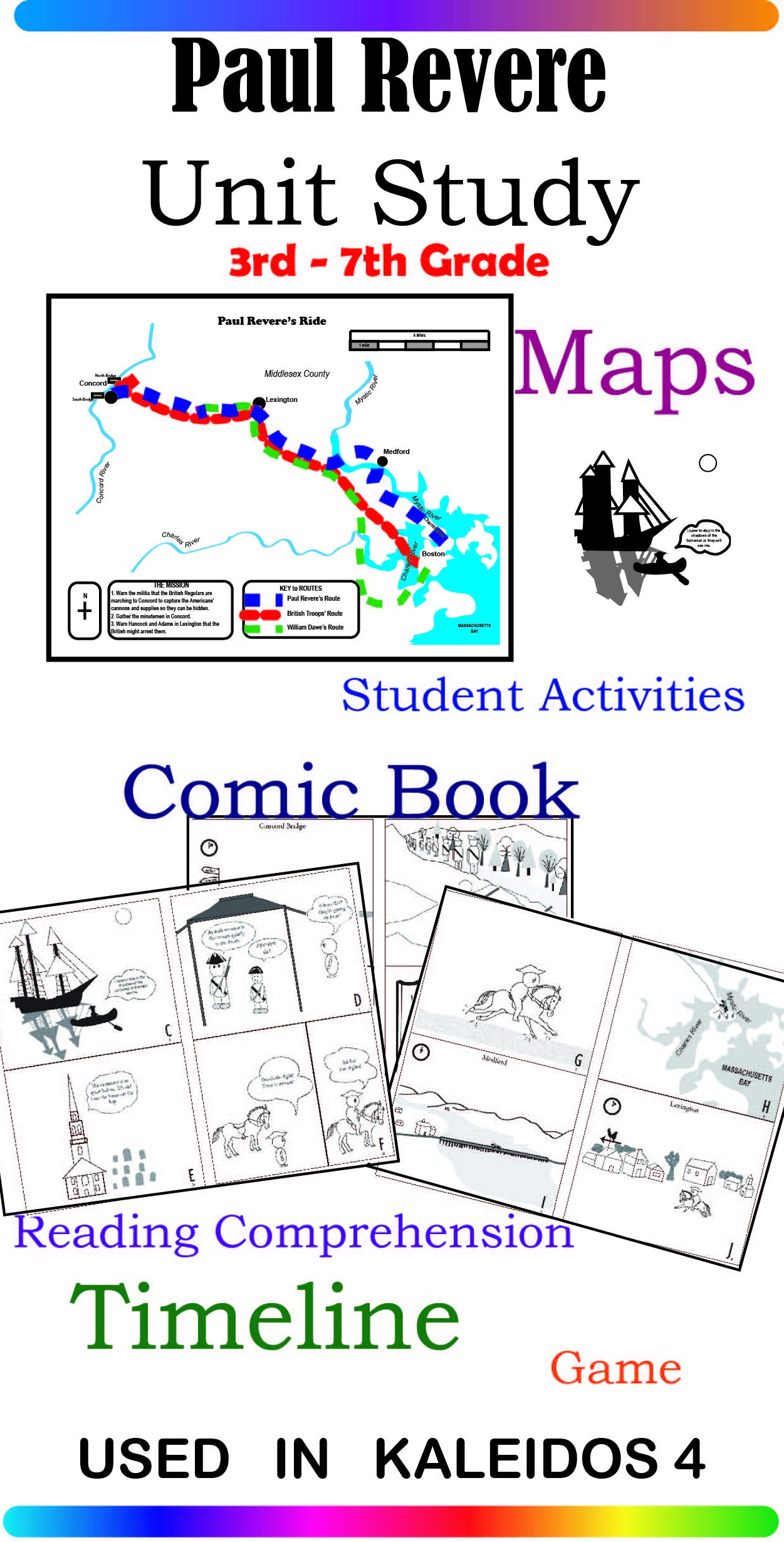

The 26 page Unit Study includes:- Historical Map of Paul Revere's Ride in color and grayscale

- Chronological Timeline of Revere and Dawe's Ride

- Longfellow's Midnight Ride of Paul Revere Poem - in sections with notes

- Paul Revere's Ride Comic Book - (corresponds to verses in the poem)

- Comprehension Questions for the Poem

- Student Activity Pages

- Suggested Hands on Activities

- Paul Revere Fun Facts Sheet

- Supplemental Audio/Visuals

- Recommended Reading List

Buy The Paul Revere Unit Study

26 Pages of Activities and Information

$2.99 Download

![]()