Finn and Hildeburg

The Tragedy of Hildeburg and Finn

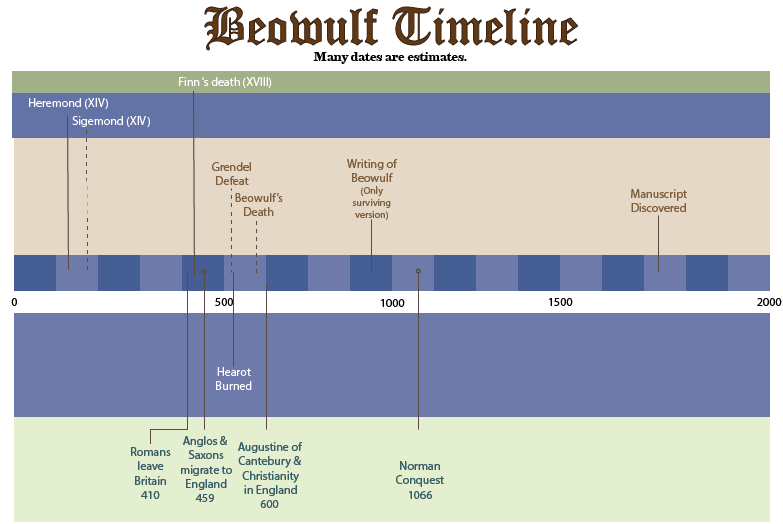

War between Danes and Frisians About 448 - 450 A.D.

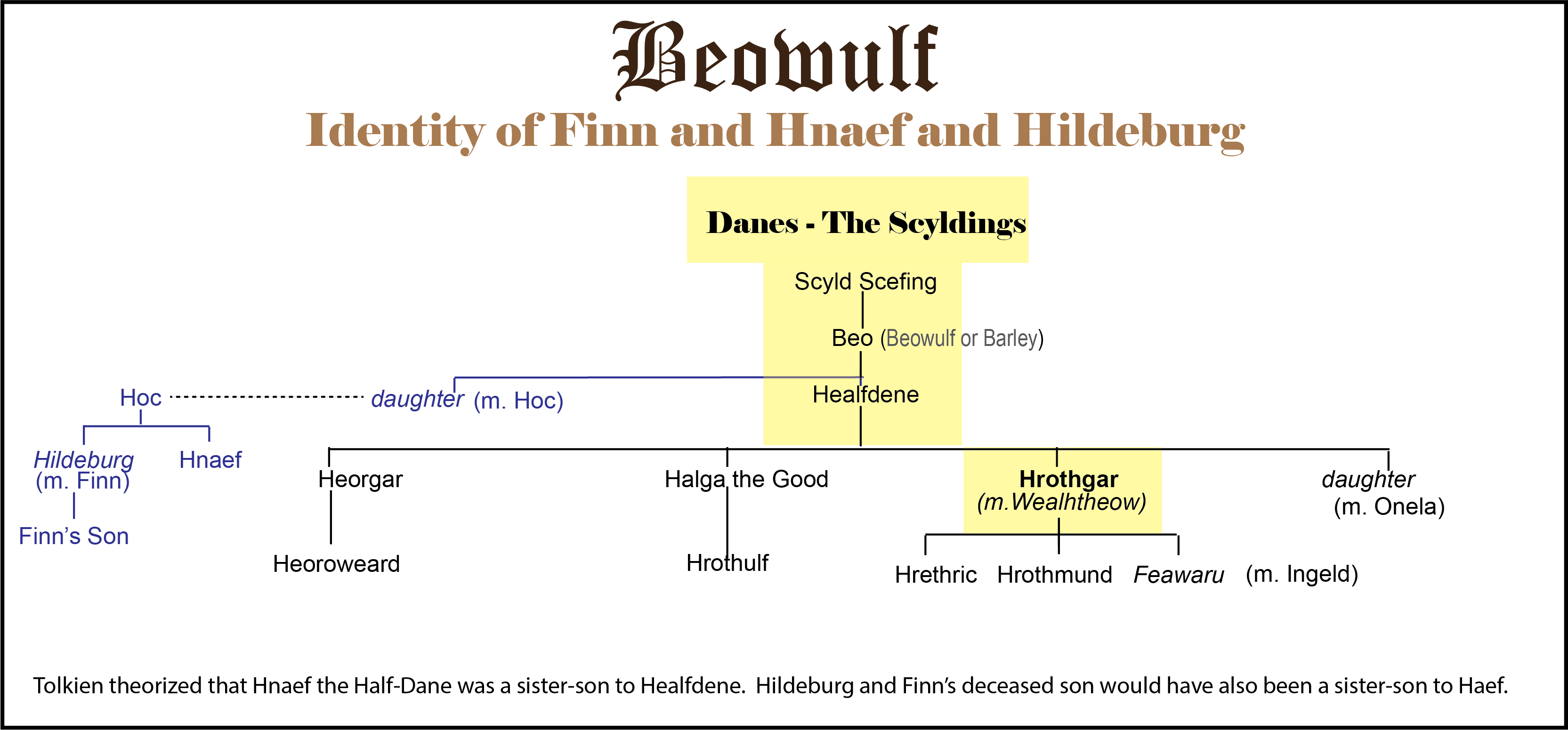

Who are Finn and Hildeburg?

Finn was the leader of the Frisian tribe on the northern coast of Europe.Hildeburg was a Danish woman from a leading family married to Finn. It was likely a peace-weaving, arranged marriage as part of a truce to secure peace between the two tribal peoples. It appears to have worked for a time, but ultimately led to tragedy when her brother Hnaef came with a group of Danes to visit her.

Their story, and the battle that ensued, is one of several story-in-a-story episodes of the poem Beowulf. It is also an event in pre-Medieval European history that, at times, is difficult to distinguish from legend.

Background of the Finn and Hildeburg Story

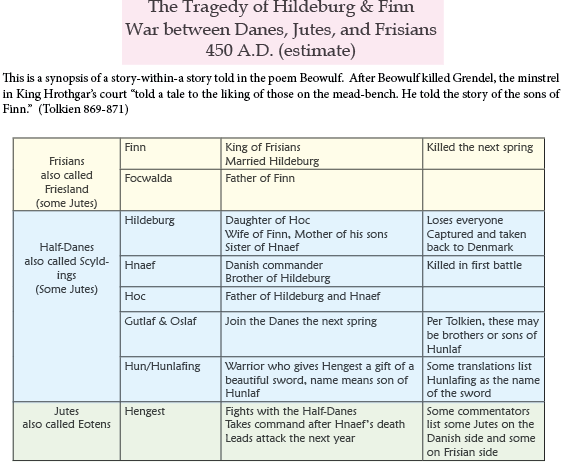

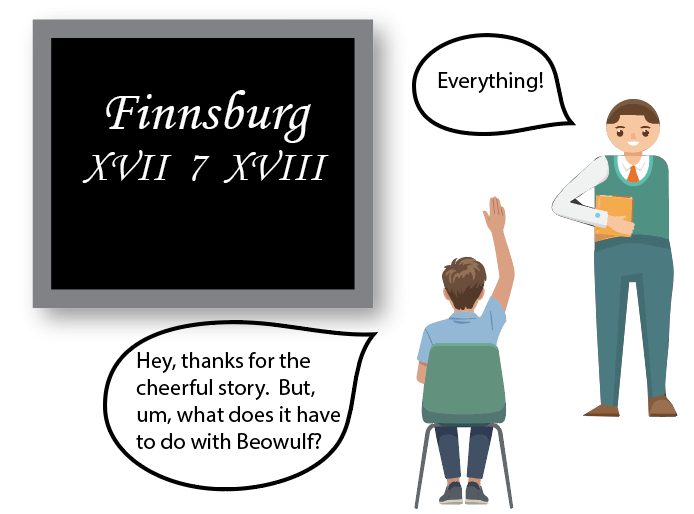

This is a synopsis of a story-within-a story told in the poem Beowulf. After Beowulf killed Grendel, the minstrel in King Hrothgar’s court recounted the story of Finn and Hildeburg:

the joy-wood (harp) was fingered,

Measures recited, when the singer of Hrothgar

On mead-bench should mention the merry hall-joyance

Of the kinsmen of Finn, when onset surprised them

(Gordon, Section VII, Lines 15-19)

OR

“told a tale to the liking of those on the mead-bench.

He told the story of the sons of Finn.”

(Tolkien 869-871)

The Story of Finn and Hildeburg

Part I: Section XVII of Beowulf

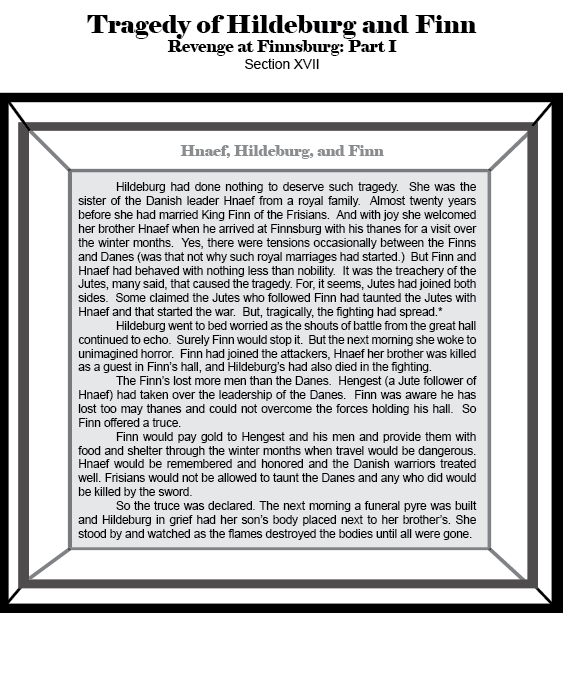

The story opens with a battle between Danes and Frisians in which one of Finn and Hildeburg’s unnamed sons is killed, as is her brother Hnaef who was the leader of the opposing side. Hengest then takes over the leadership of the Danish army.The next morning Finn is aware that he has lost enough warrior’s (thanes) that he cannot win against the Danish forces. So Finn offered a truce that he would share the land, castle and pay gold to Hengest and his men. Hnaef would be remembered and honored and the Danish warriors would be treated well and quartered. Frisians would not be allowed to taunt the Danes and any who did would be killed by the sword.

A truce was declared. The next morning a funeral pyre was built and Hildeburg in grief had her son’s body placed next to her brother’s. There was much wailing and grief as the destructive flames brutally destroyed many bodies until all were gone.

Part II: Section XVIII of Beowulf

The Frisian warriors returned to their home and Hengst and his warriors dwelt with Finn over the winter, unable to travel due to the dangerous storms at sea. But Hengst thought more about vengance than home. He was given a sword by Hunlafing, a Danish warrior. Gutlaf and Oslaf joined Hengest and they attacked the Frisians, killing Finn. Hildeburg was taken to Denmark by sea along with all the treasure they could find in Finn’s hall.Significance of the Finn Episode in Beowulf

Contrast in Mood and Tone

Notice these words in the poem that indicated the joyous celebratory mood of the sixth-century minstrel performing the morning after Beowulf killed Grendel:- joy-wood (harp) was fingered

- merry-hall joyance (of the men as they listened to the story)

So what's happening here? Well, the warriors are in a good mood and happy to hear the old story of Finn, who finally got what he deserved, the old-rat. You can see them lifting their mugs of ale and yelling "hear, hear."

The sixth-century mead drinkers in the tale respond differently than the tenth-century mead-hall goers this version was performed for.

The tenth-century listeners knew the rest of the story.

Tragedy About to Happen

The Finn Episode is immediately followed by a scene where Queen Wealtheow states she knows their nephew will always treat King Hrothgar's sons well if anything should happen to him. It is a plea. Then she turns and looks at her sons sitting on the bench with Beowulf. (If it was a movie, the ominous music of foreshadowing would start now.)The tenth-century listeners caught the parallel between Queen Hildeburg and Queen Wealtheow. For in a short time after these events, the historical Hrothgar would be betrayed, Hearot Hall burned, and his sons killed. By the nephew. And Hrothgar's son-in-law. Anyway, these family feuds could get a bit messy.

Themes in Beowulf

Beowulf, it turns out, was the "Original Family Feud" show. Many readers are confused by the numerous digressions (fancy name for a story-in-a-story that temporarily leave the main plot.) But these digressions have a similar theme of women's loss through blood pacts and family revenge popular in the old-north culture.The author, whom we call "Poe X", was a tenth-century Christian who used the story of Beowulf to draw a distinction between the pagan heroes of the past and the Christian faith. Many traits were valued by both their pagan ancestors and the new Christian religion: bravery, generosity, kindness.

What is not the same: revenge and pride. Those were valued by the heroic code of the old pagan culture but contrary to Christian belief.

Literary Signficance of the

Frisian Battle in Beowulf

This Finn Episode underscores at least three themes in Beowulf.

Revenge

The Beowulf author contrasts the pagan view that exalts revenge with the Christian view that shows its tragic consequences. Both of the settings in Beowulf (Hrothgar's court and Hygelac's court) were destroyed by revenge and family blood pacts. Most of the digressions in the Beowulf poem support this theme.Setting: The Mead Hall

Poe X develops a unique mirrored genre: the story of a mead hall told by a minstrel singing in a mead hall. This produced interesting effects that are often missed by modern readers busily trying to decipher old-fashioned words.The Finn Episode demonstrates a battle within the mead-hall setting, as well as a long sojourn by Hengest and his followers who have to live through the long, dreary winter in that hall while dreaming of - you guessed it - revenge!

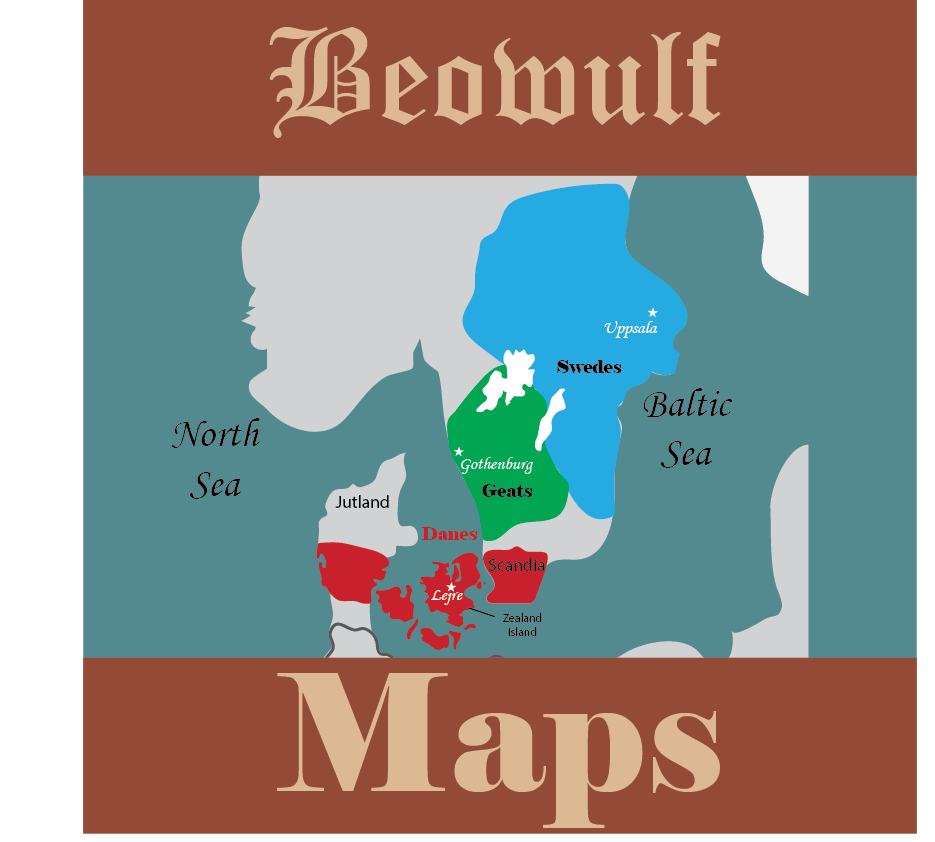

Tribal Identify and People Groups

This story about Finn would be of significance to the Danish people in Hrothgar's court less than one hundred years later. It was also significant to the Anglo-Saxons of the tenth/eleventh century who had migrated off the Danish peninsula. (See section below.)Background of Finn, Hnaef,

Hildeburg, and Hengest

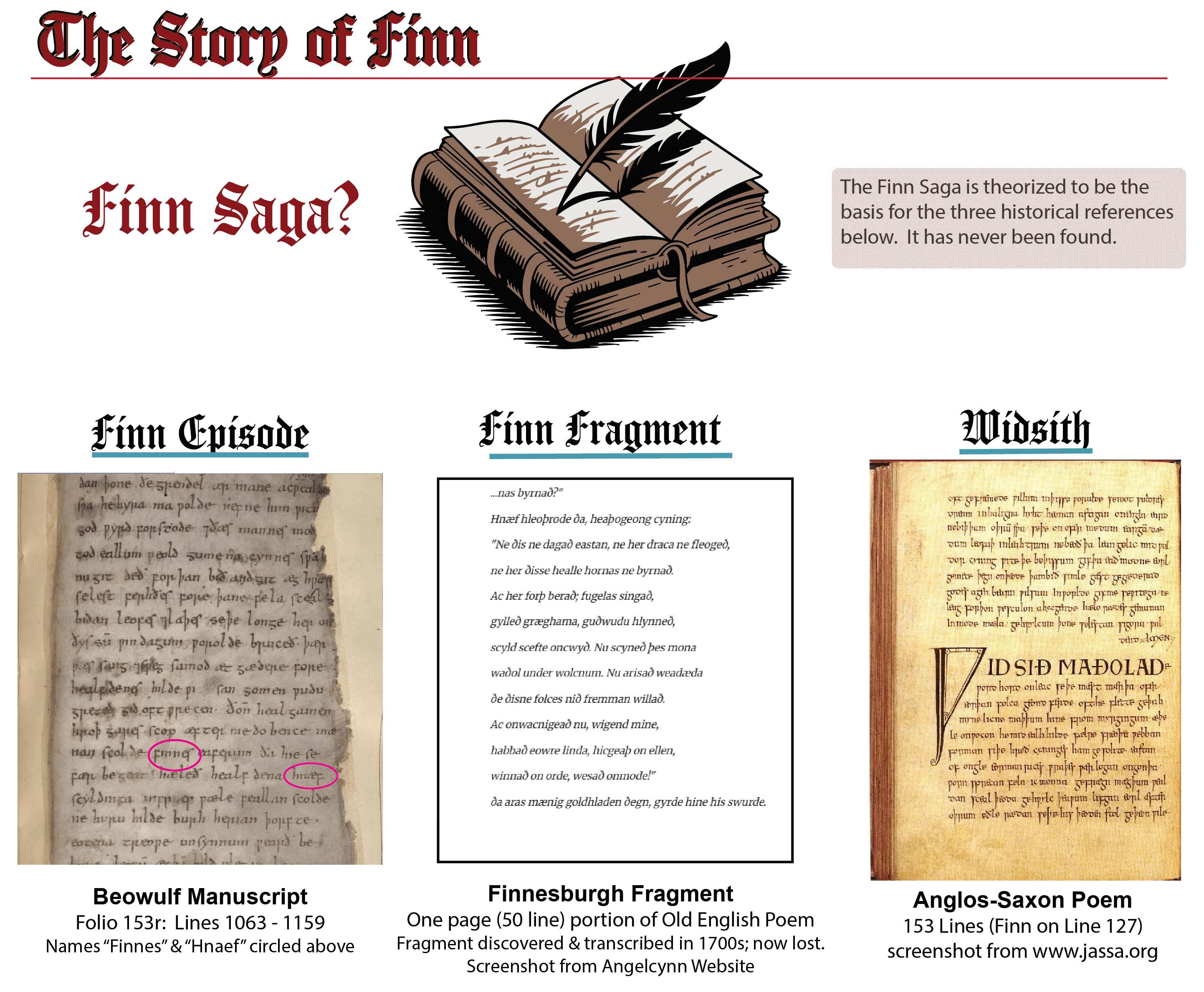

- "Finn Episode" - these lines in Beowulf

- "The Finn Fragment" - a short portion of a different poem which gives more detail of the battle

- Widsith - a one-line mention of the characters in a long poem about kings of this era

There is one other historical record of Finn, but it doesn't mention this battle. The old Anglo-Saxon poem Widsith was written between 550 and 900 A.D. (depending on the scholar one reads.) It is a list of rulers of different Germanic tribes in the early sixth century and lists our Finn as the Frisian leader on Line 27:

Finn Folcwalding, the kindred of the Frisians

In addition to these two fragments, there are other references to Hengest in early British history:- Ecclesiastical History by Bede (731 A.D.)

- Anglo-Saxon Chronicle (449 A.D.)

- Historia Brittonum by Nennius (c. 830 A.D.)

- Historia Regum Brittaniae by George of Monmouth (1136)

- Layamond's Brut by Layamond (c. 1190)

It also should be noted, that Hengest led the Anglo immigration to Britian in 449 A.D. making him an English forefather (assuming he is the same Hengest, which according to both Webster and Tolkien is likely.) Historians also place the date of the migration a few years later than the traditional 449 date given by Bede which is the reason we list the Frisian Battle about 450. But hey, what's a year or two between friends - or enemies as the case may be.

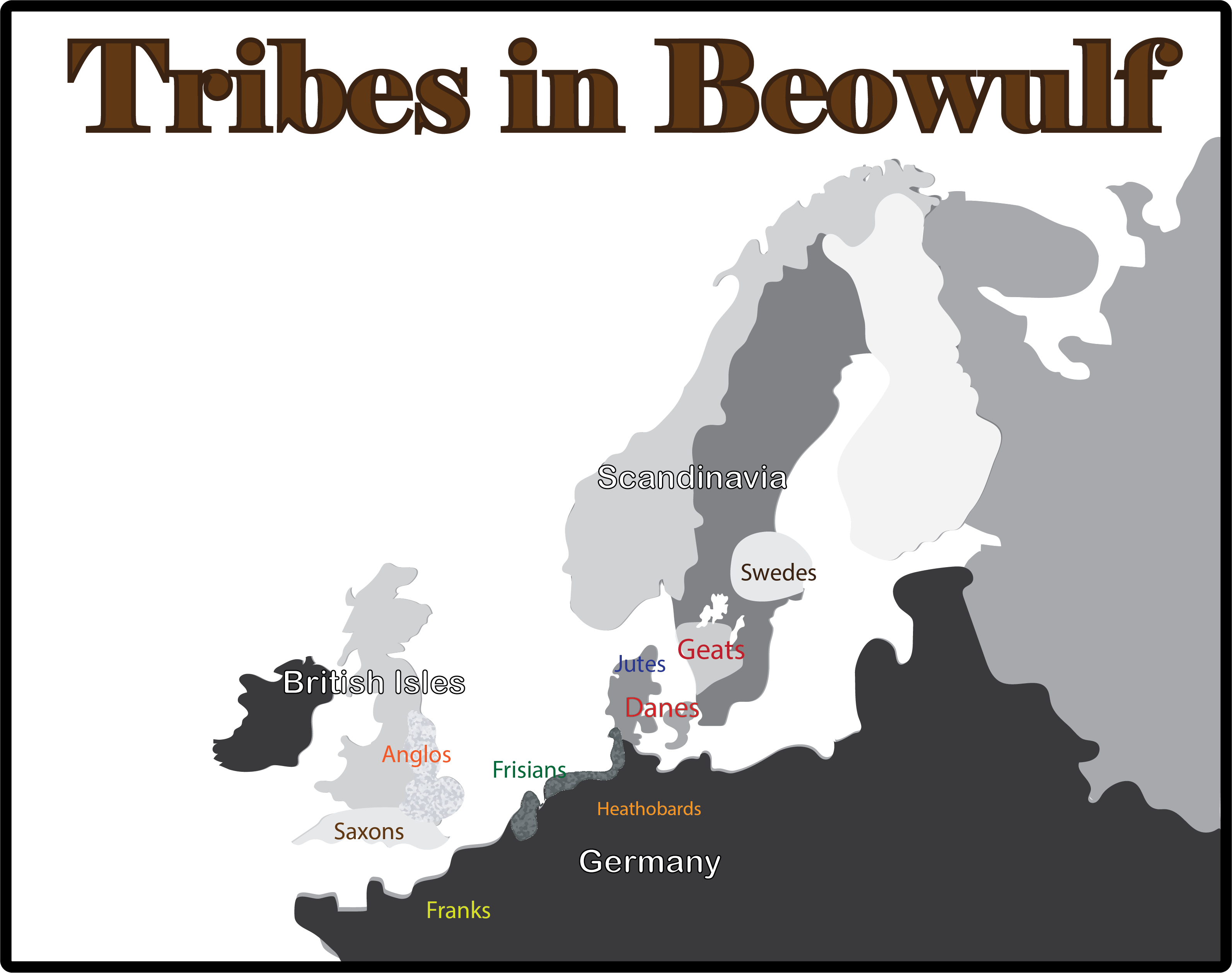

Significance of Tribes in the Finn Saga

So we have a total of three tribes in this battle:- Finn, King of the Frisians

- Hnaef, leader (maybe king?) of "Half Danes"

- Hengest, from the Jutes

Controversy abounds on that question. Our sources complicate matters.

Difficulty with the Beowulf Episode

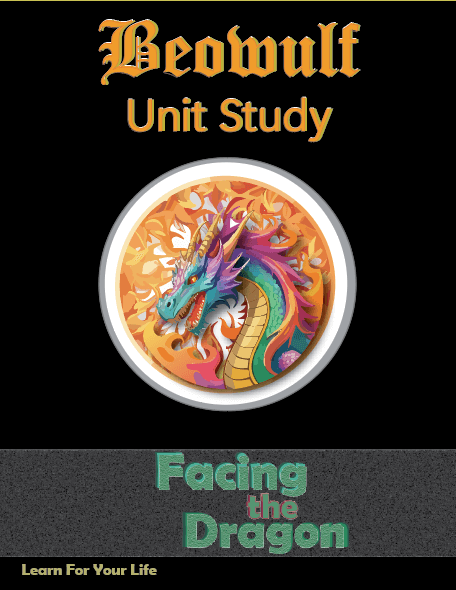

To begin with the Beowulf poem gives us an "indirect quote" of the lay sung by the sixth-century minstrel in Hrothgar's court. He doesn't tell us the whole story, but just hits the high points in 167 lines, convinced that all his hearers in the Danish hall known the story fairly well. Too bad for us - for there is plenty we wish to know.Difficulty with the Finn Fragment

Then the Finn Fragment as we have it is shorter - only 45 lines. It's actually a pretty exciting piece of battle-lore as Hnaef's sixty retainers hold the hall for five days. It starts in the middle of a sentence, with the gables burning, and ends in the middle of sentence with a wounded attacker being challenged. The poem in its entiretly is likely ten times the length of the fragment we have and undoubtedly would answer many of our questions (about Jutes and other issues.)JRR Tolkien and Finn

We have been bequeathed, fortunately, by Professor J.R.R. Tolkien and his post-humous publication of his teaching notes in Finn and Hengest: The Fragment and the Episode (editor Alan Bliss) with a translation, commentary, and reconstruction of the material. His position was that there were Jute warriors on both sides: some followers of Finn and the Frisians, and others who were followers of Hnaef and the Danes. He does a detailed analysis of the various words and their endings as well as this mysterious line in Beowulf:Nor had Hildeburg cause to praise the faith of the Eotens (Jutes)

Tolkien's analysis is that it is likely the battle was started not by either the Frisians or the Danes, but by the different factions of Jutes. He particularly suspects that the Jutes in Finn's Frisian court were offended by Hengest and his Jute followers who had attached themselves to Hnaef's group of Danes. His book mentioned above is highly recommended for any desiring a reconstruction of the political alliances and tensions between the groups and named-individuals.Historical Significance

In spite of our ignorance about who was on what side and what started the conflict, there is historical value to this tale apart from it's role in Beowulf.These were some of numerous Germanic tribes that had migrated out of the German mainland: Frisians, Danes, Jutes, (as well as Anglos and Saxons who aren't in the Finn Saga but are in the Beowulf drama). The Jutes, who had settled the peninsula named Jutland (now called Denmark) were the first to get pushed aside in the migration described by all the sources quoted above. We see them in the Finn Saga as a leaderless group but still with their identity, alliances, and conflicts. Jutes migrated with Anglos and Saxons to Great Britain, but they blended in eventually and their distinct ethnicity died out.

This isn't to reduce their significance, because Hengest the Jute - the same in the saga, is considered one of the forefathers of England. And this drama between he and Finn is what led him to lead a group to migrate to the British Isles. (Well, at least that's an educated guess. We have nothing written by him to tell us exactly what was going on in his mind through all of this.)

Meanwhile, the Frisians lasted longer than the Jutes as a distinct group. But their location on the northern coast led to their harrassment by pillaging Vikings (i.e. Danes) in the two to three centuries following this tale. Friesland is currently a province of Netherlands, and probably peopled by some of Finn's descendents.

The Danes, of course, have kept a pretty good hold on the country of Denmark. And they have settled into the modern world and given up pillaging their neighbors, for which we can all be grateful.

And those Anglos and Saxons (and the Jutes who accompanied them) made their mark on world history as well.

Which is the point...or at least part of it. Beowulf is the story of the Danes who would become a world power in the following century and the Anglo-Saxons who would become the English. It is also the story of Beowulf's people, the Geats, as well as the Frisians and the Wulfings, and the Heathobards and others who would not. The Beowulf poem closes with the prediction that the Geats, like the founders of the dragon's ancient treasure hoard, would cease to be.

Pride, it would seem, really did go before a fall.

Finn and Hildeburg in the Beowulf Unit Study

The story of Finn, Hildeburg, and Hnaef is one the stories-in-a-story in Beowulf (as well as the second part follow up about Hengest.)

- It demonstrates that it is a story-within-the-larger story.

- It describes the action of the historical narrative.

One difficulty for modern readers is that these historical narratives are unknown. It is obvious that the poet thought the listeners knew the story, so he didn't bother to spell it out. This makes the action-line difficult to connect. Most students miss the action of the historical narratives and hence miss the entire point that the poem is trying to make with the tales of monsters and dragons.

Facing the Dragon narratives the historical events in a story format to acquaint the students with the characters before they are read in the poem. That, of course, is how the original audience experienced the poetry.

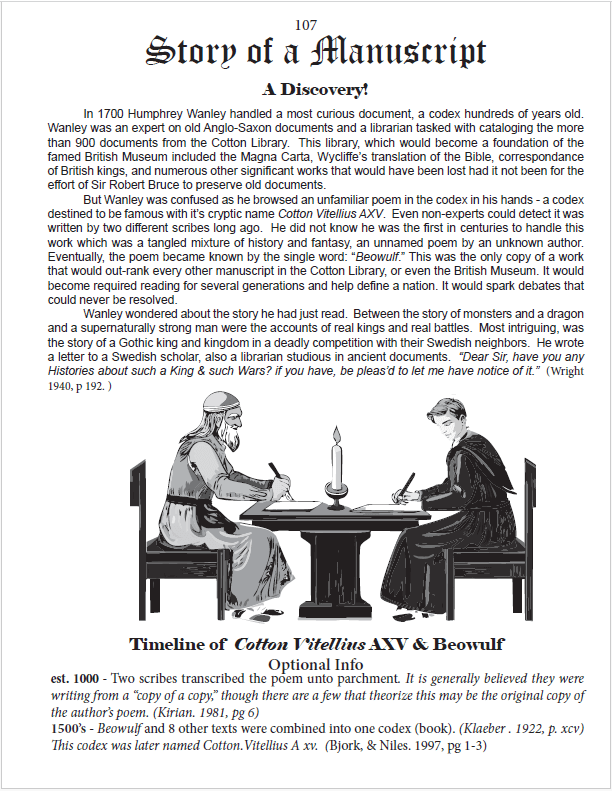

Get the Beowulf Unit Study

Unlock the action plot, history, and debates of the ancient tale.

Available in Paperback OR Printable Download

253 pages

(Includes Student Pages, Teacher Key, References, Maps, Charts and More!)

Print It Now

![]()

$5.99 Your link to print will last for five days.

Ready-in-a-minute lesson plans can be used with any translation.

Easy-to-read summary for each section.

Softcover Edition - Mailed to You

The same pages are in the softcover book and the printable file. Keep your papers bound together and use this book for years to come. It will be your go-to-guide for all things Beowulf!

![]()

17.95 Soft Cover Manual

Mailed to You

Beowulf Pages

Check here for all things Beowulf.

About Our Site

Hands-On Learning