Oliver Twist and Jacob's Island

Curious about this mysterious place in Oliver Twist called Jacob's Island, where the notorious Sikes meets his deserved end? And how can the island of Great Britain have an island inside London? Unlock the enigma of this perplexing place of Jacob's Island, Mill Pond and Folly's Ditch.What Is Jacob's Island?

Jacob's Island was not really an island in the typical sense. A series of man-made ditches off of the River Thames were created to run tidal mills. At high tide when the creek-sized ditches filled with water, a sluice gate closed off the flow of water keeping the water level high. As the moving water was allowed to slowly drain back into the Thames, it powered the mills along the river front and around the ditches. Behind and between these mills were closely packed houses.

But it was not always a rotting slum. Let's explore the history of this intriguing piece of geological, sociological, and literary history known as Jacob's Island.

Discovering Jacob's Island

One always understands a story better when the geography is understood. The first time I read Oliver Twist, I wrote notes in the margin to look up Jacob's Island - enticed by Dickens' perplexing description. Finding the answer to this riddle was harder than expected.It took some real hunting to find out about this place, and its intrigue grew with the research. For the information on this page, I am indepted to a number of fellow curiosity seekers, all of whom are British and have the distinct advantage of not having 3000 miles of ocean between themselves and the mysterious destination. In addition, they have combed through some old tomes to find references and pictures that otherwise would have been buried to us. I have tried to give credit to them on this page.

Location of Jacob's Island

Historical Timeline of Jacob's Island

715 A.D.

Vermundesei Monastery

An ancient monastery, long gone with virtually no remaining traces, was built in the general area and slightly west and south of Jacob's Island on the southern bank of the River Thames. The area was predominately pasture at that time. The existence of this long-gone monestery would have no interest for us, except that a later monastery did contribute significantly to the history. The later 11th century monastery may have been built on the exact site as the original.

1082 A.D.

Bermondsey Abbey

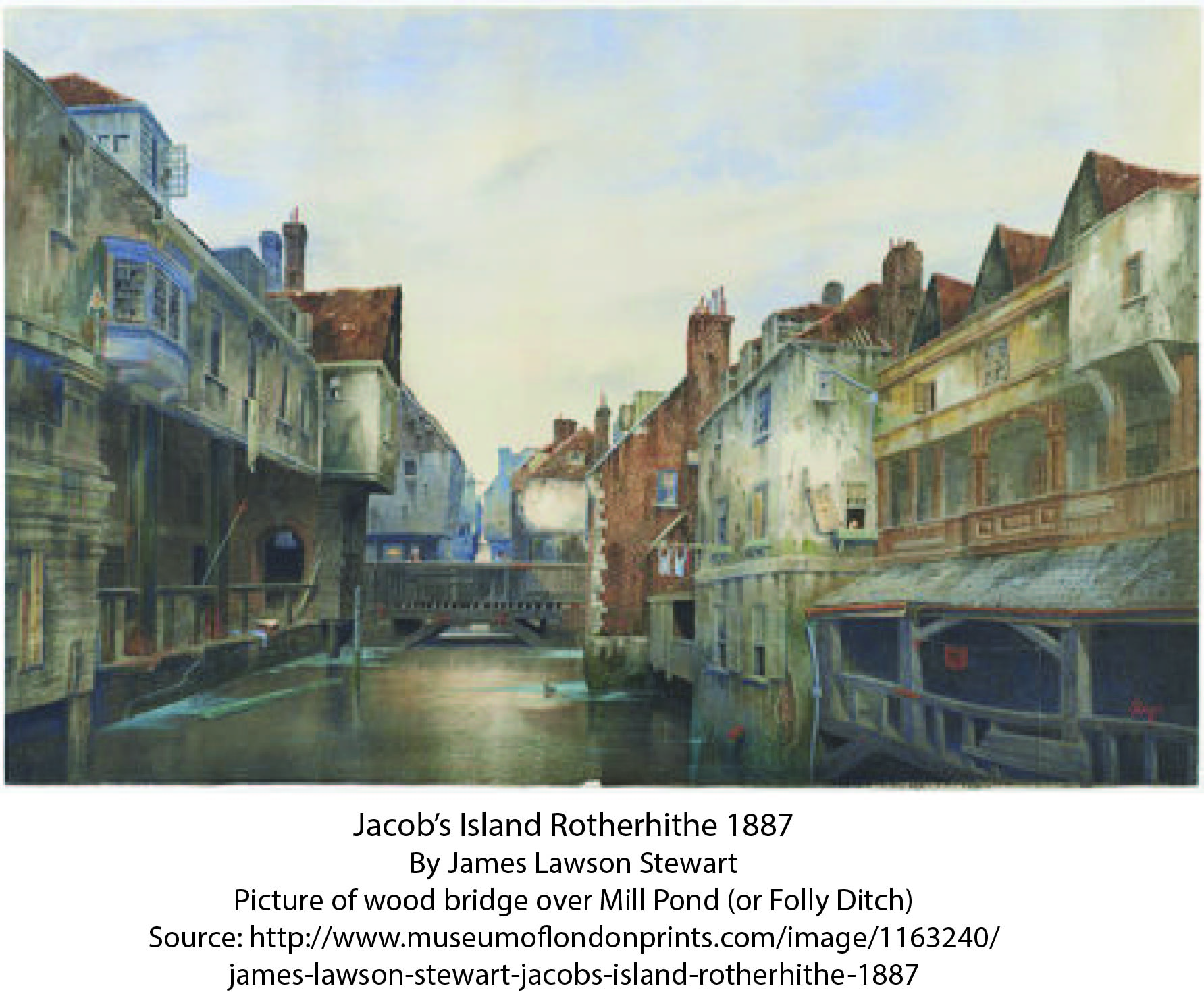

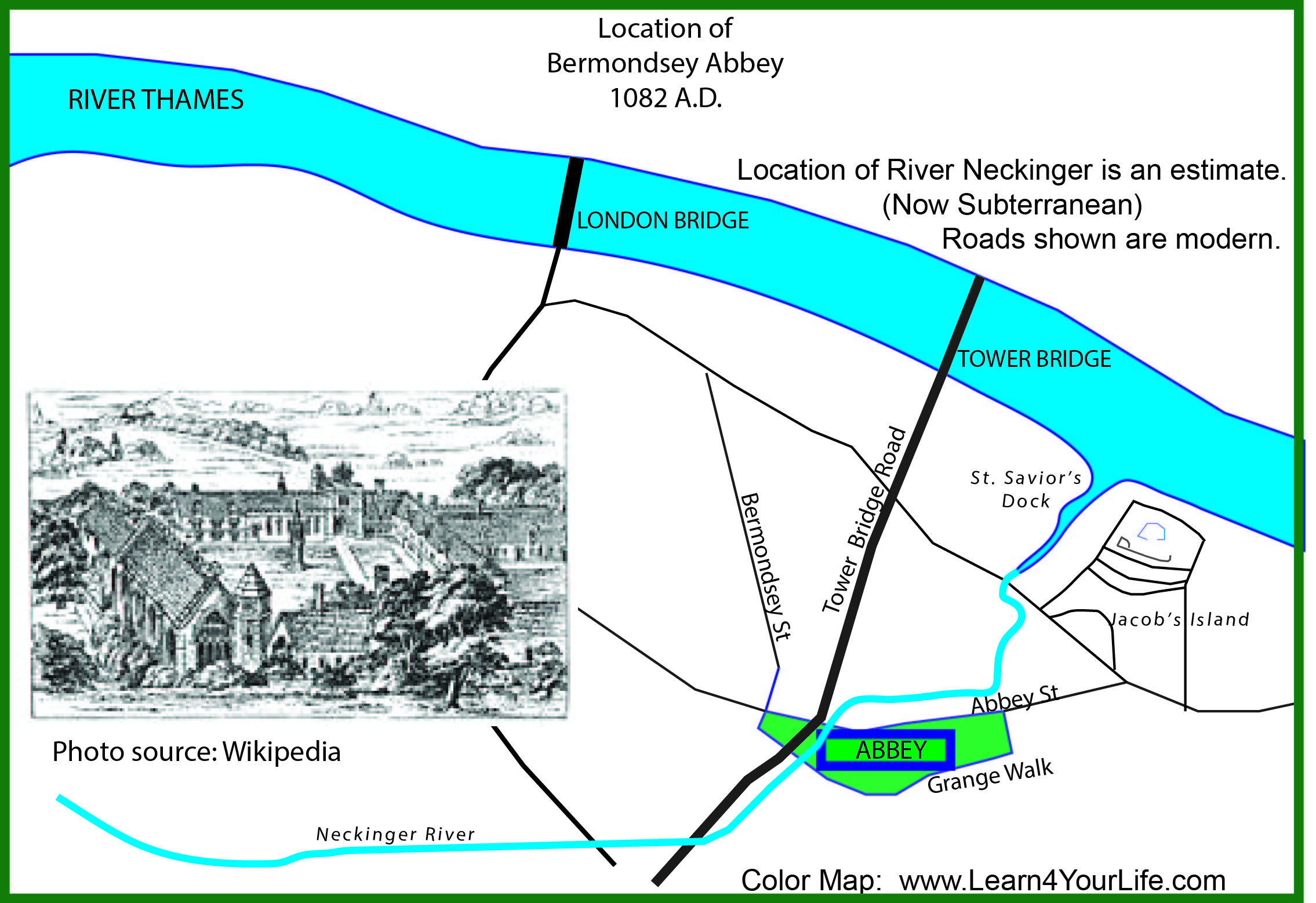

The Benedictine Priory of St Saviour at Bermondsey was built in 1082. According to the site London Remembers, the Abbey was between Bermondsey Street, Abbey Street and Grange Walk.1 See map below. Compare to the modern map above.

1200s

St. Saviour's Dock & and Medieval Mill

To meet the needs of their own community, the monks of Bermondsey Abbey made a few structural changes that impacted the later history. The inlet of the Neckinger River was enlarged where it entered into the River Thames. The inlet was turned into a dock and named St. Saviours Dock by the monks. This dock still exists and is in use. (See the map above for the enlarged dock.) At this point in time, the Neckinger River could be navigated from the Abbey to the Thames via the Neckinger and St. Saviours Dock.

1536

End of Monastery & Water Mill

Diversion of the Neckinger

With the political and religious turmoil during the reign of Henry VIII, the Dissolution of the Monestaries terminated the Roman Catholic monestaries in England, including The Bermondsey Abbey. The Mill of St Saviour was changed from a windmill to a water mill, supplying the local community with drinking water. According to Somerville5, the site of the original mill later became a gunpowder factory, a paper mill, and eventually (in Dicken's time) a lead mill. Undoubtedly, the monks of Bermondsey Abbey would never have imagined the changes their wind mill would undergo.

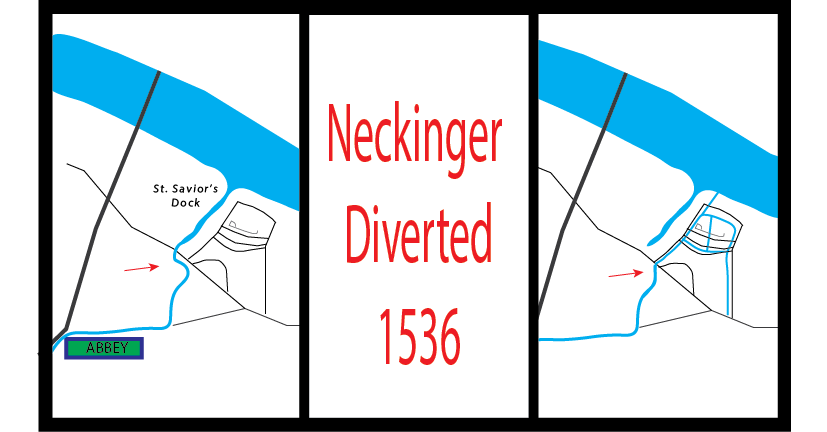

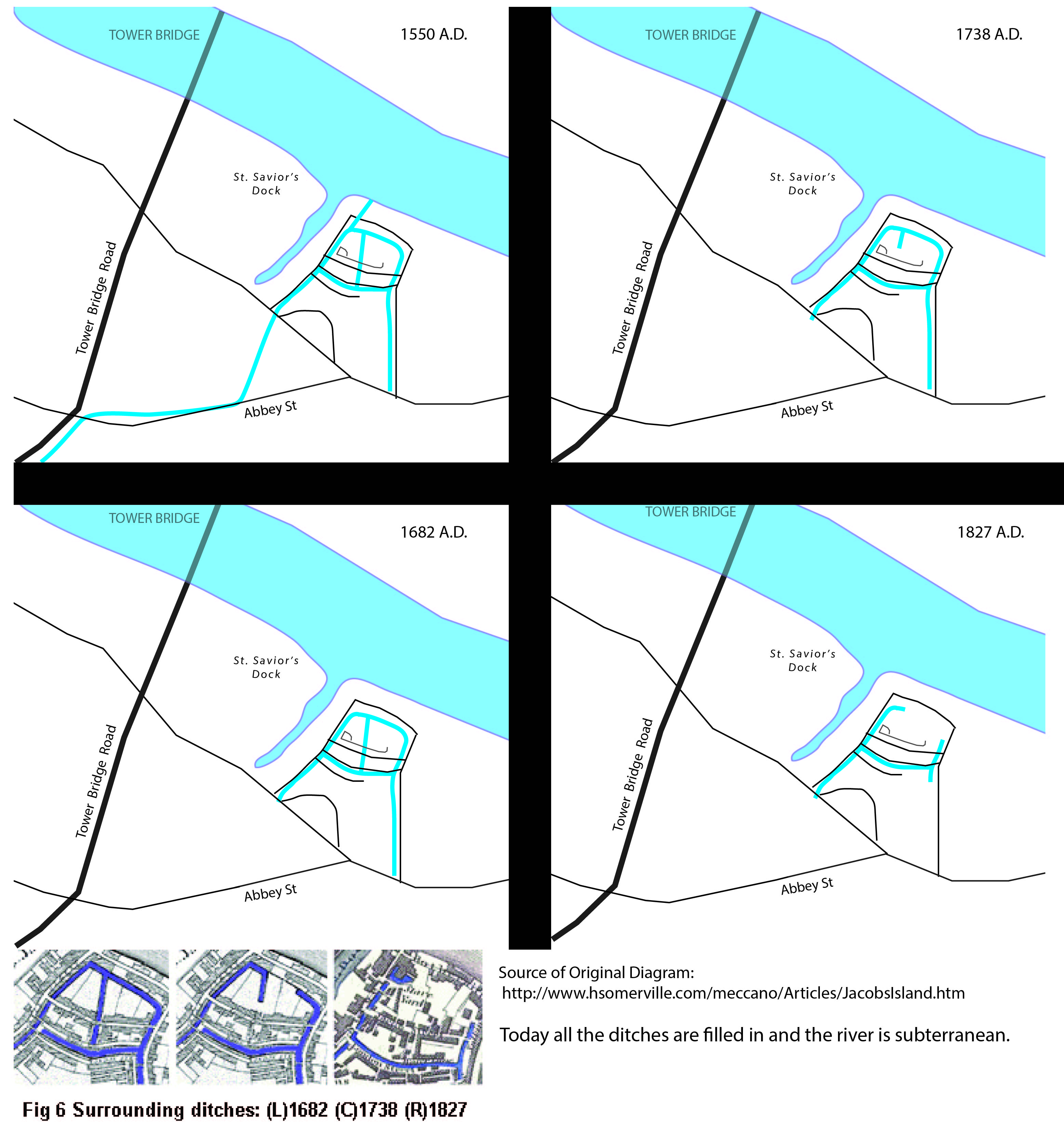

Another significant change occured in 1536 with the construction of the water-mill. The Neckinger River was diverted 100 yards east of St Saviours Dock and entered the River Thames from that point. This diversion of the river created the water flow that would power the industry for a few hundred years, but eventually become stagnant ditches to the detriment of the residents.

The diversion of the Neckinger also disconnected the river from St. Saviour's Dock. The dock became lined on three sides with houses and factories as it is to this day.

This diversion of the River Neckinger was geologically significant. Previously the river ran its 2.5 kilometer course from Southwark, towards the location of Bermondsey Abbey, then emptied into the Thames approximately 35 miles west of where the Thames empties into the English Channel.1 This was a jolly good place to hang pirates, history informs us, and hence gave the Neckinger its name.2 With its diversion into the Mill Pond of Jacob's Island, the Neckinger was no longer the same brisk river, and apparently another location for pirate executions needed to be found.

1550 - 1650's

Flourishing Community

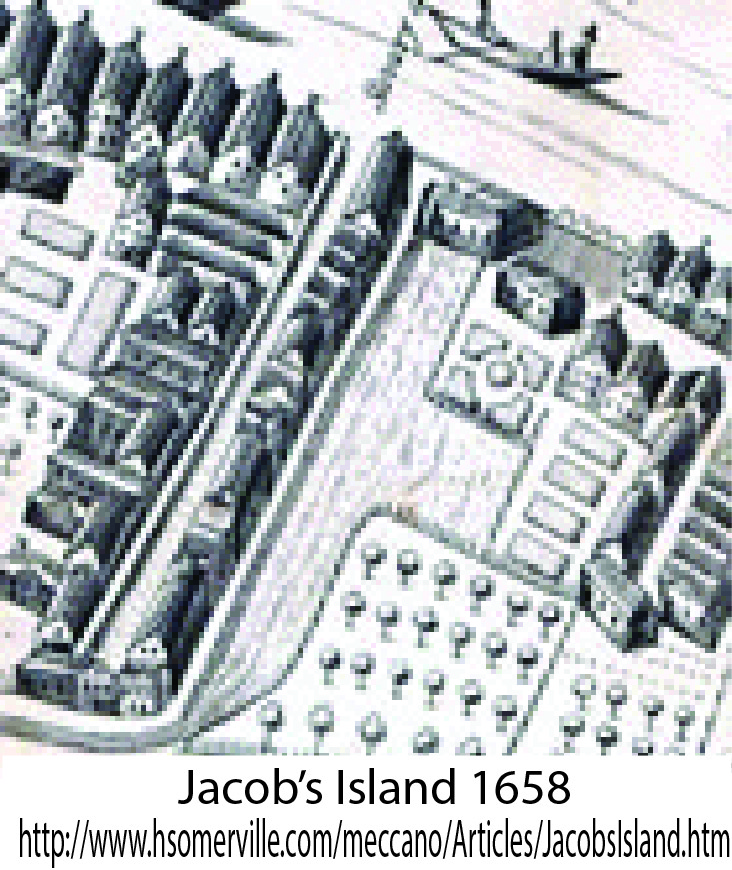

With industrial changes on the horizon, this picturesque setting is about to change. More man-made ditches are dug in the naturally marshy-ground and connected to the T-shaped mill pond. These circular and criss-crossing waterways are fed by two sources: the Neckinger River, flowing northward from the south of Jacob's Island; and the River Thames with its twice daily tidal rises.

1650-1800

Industry

Quote by HSomerville: By 1682 Jacob's Island had become a densely built-up commercial area of factories, tanneries, warehouses and mills, with houses, shops, small workshops and workers' tenements built between them. The bank-side houses owed their curious features to their position; the ditches, which served both as water supplies and sewers, provided open space to build galleries for access, overhanging sleeping chambers and privies.

The water-powered mills hosted a mixture of industries including a significant ship building trade. Less than a mile from Jacob's Island stood the Mayflower Pub of Rotherhithe, today the oldest standing pub on the Thames. This was the place where a small, unpretentious commercial ship was moored before heading to Plymouth to pick up its 102 passengers and begin its epic trip across the ocean.4 Indeed, in the time to come Jacob's Island and Rotherhithe would compete for the shipbuilding business, a competition the residents of the man-made island were destined to lose.

According to Somerville, by 1792 a third of England's leather would be processed in Jacob's Island. While a welcome economic development, tanneries are not pleasant smelling as the leather is processed in animal urine and feces. It was this less-pleasant change that is believed to be the origin of St. Saviours Dock being ironically called Savory Dock.

Somerville's quotes above demonstrate how this area has moved from pastoral, to small village, and now an industrial urban complex. It is based on a water system that provided water for homes, ran the mills, and created an open sewer system. The stage has now been set for our infamous scene. But it is not infamous yet. While very urban, this area is alive with trade and industry. There are jobs to be had, a community that was thriving, and running water for all.

1800

Unhealthy Conditions

Economic Decline

A number of factors contributed to the decline of Jacob's Island, not the least of which was economical. The ship building industry had moved slightly downriver to the west to Rotherhithe, whose northeast projection into the River Thames was prefered to the mills on Jacob's Island. With the loss of employment, the descent into poverty started.Stagnant Water: A mill was built between the mill stream and the Thames, cutting off the major supply of water to the region. In addition, many of the ditches were filled in to make room for other factories.

Sewage: It was more than just standing water: the ditches were cess pools. Not only were the privies of the inhabitants of Jacob's Island dumped into the man-made ditches that created the island, but the urbanization of London had crossed the Thames and moved south of the Bermondsey region. Sewage from much of London's population was dumped in the street, and made its ways to the stagnant shores of Jacob's Island.

Mid 1800's

Slum of All Slums

Crime: With standing putrid water, loss of jobs, and deteriorating homes and factories, the area began to decline rapidly. Criminals began to hide out in the rotting buildings abandoned by the civilized part of London. Crooked inhabitants created secret doorways and passageways, now a cross-ways of crime instead of water. For those residents who weren't criminals but simply the destitute with no place else to go, the influx of London's gangs was surely the end of what had once been a good place to live and raise a family. No more. This is the area that Dicken's visited and this is the Jacob's Island described in such horrific terms in his book. They must have powerful motives for a secret residence, or be reduced to a destitute condition indeed, who seek a refuge in Jacob's Island.13

1849 & 1854

Cholera Epidemics

Somerville states that in 1849 Jacob's Island had a population of 7,286.5 Remember we are talking about a 130 x 130 meter piece of land. Think of a football stadium. With crowded conditions, standing water, and dead carcasses from the tannery, its a disaster waiting to happen.It happened.

Somerville quotes a contemporaneous article from 1849 Chronicle:

Out of the 12,800 deaths which, within the last three months, have arisen from cholera, 6,500 have occurred on the southern shores of the Thames; and to this awful number no localities have contributed so largely as Lambeth, Southwark and Bermondsey, each, at the height of the disease, adding its hundred victims a week to the fearful catalogue of mortality. Any one who has ventured a visit to the last-named of these places in particular, will not wonder at the ravages of the pestilence in this malarious quarter, for it is bounded on the north and east by filth and fever, and on the south and west by want, squalor, rags and pestilence. Here stands, as it were, the very capital of cholera, the Jessore of London - JACOB'S ISLAND, a patch of ground insulated by the common sewer. Spared by the fire of London (referring to the Great Fire of 1666), the houses and comforts of the people in this loathsome place have scarcely known any improvement since that time. The place is a century behind even the low and squalid districts that surround it.

A second cholera outbreak occured in 1854. After that the ditches were finally filled in by the city of London. This was indisputably the right decision.

1861

Fire

The Great Fire of Tooley Street started June 22, 1861 at Cotton's Wharf on the Thames close to London Bridge. The fire raged unchecked for two days before it could be contained, but it took two weeks for it to be totally extinguished.At the end, 20 warehouses were destroyed, many homes and shops burnt, and the superintendant of the fire department (James Braidwood, the father of modern municipal fire fighting) was killed. Two million pounds of damage was done and an unknown number of lives lost in a fire said to be the worse since the Great Fire of London in 1666.

While other areas of the city were burnt, the rotted homes and abandoned mills and factories of Jacob's Island were devastated. 6

1875

Urban Renewal?

With the ditches of water filled in and many warehouses and homes destroyed by the fire, Jacob's Island was no longer an island.The final demise of this unique community occured through city planning. Almost all buildings that survived the fire were torn down. New warehouses and tenement buildings were built.

Questions were, and still are, asked about the ethics of the urban planning of Jacob's Island.

- Were the wishes or needs of the former residents considered? What happened to them? Who gets to make the decisions?

- Should a community with its own identify and own history be eliminated by city planners?

- Is gentrification (fixing up a poor neighborhood so residents with better means move in) good or bad?

Or almost gone. One of the only buildings to have survived the changes since Dicken's era was an ale house: The Ship Aground. How fitting that a pub was the only part of Jacob's Island that stood into the beginning of the century. It, too, is now gone.

1944

WWII

The few remains of Jacob's Island that had survived fire and city planners were eliminated by the Germans. The Luftwaffe Blitz hit the area hard. Jacob's Island was annihilated.

Gone but not forgotten. New generations of readers traverse London's streets following the innocent Oliver and the conniving Fagin or his gang. Here their journey takes them to Mill Pond and Folly Ditch on Jacob's Island.

"What is this place," they wonder, convinced by Dicken's words that the area he describes is one he has actually seen. One searches long and hard to find a map that confirms it did exist once. Exist, it did.

But could it really been as bad as Dickens described? Dig a little deeper and you will find it was actually worse.

Life on Jacob's Island

Robert Tobin writes about his own search for Jacob's Island. He quotes a number of first hand accounts more or less contemporaneous with Dickens.6 These include Henry Matthew, a social reformer, whose descriptions of the community were published in the Morning Chronicle in 1849 with an article entitled "A Visit to the Cholera Districts of Bermondsey”.7“On entering the precincts of the pest island, the air has literally the smell of a graveyard, and a feeling of nausea and heaviness comes over any one unaccustomed to imbibe the musty atmosphere. It is not only the nose, but the stomach, that tells how heavily the air is loaded with sulphuretted hydrogen; and as soon as you cross one of the crazy and rotting bridges over the reeking ditch, you know, as surely as if you had chemically tested it, by the black colour of what was once the white-lead paint upon the door-posts and window-sills, that the air is thickly charged with this deadly gas. The heavy bubbles which now and then rise up in the water show you whence at least a portion of the mephitic compound comes, while the open doorless privies that hang over the water side on one of the banks, and the dark streaks of filth down the walls where the drains from each house discharge themselves into the ditch on the opposite side, tell you how the pollution of the ditch is supplied.”

“The water was covered with scum almost like a cobweb, and prismatic with grease. In it, floated…carcasses of dead animals, ready to burst with the gases of putrefaction”

Across some parts of the stream whole rooms have been built, so that house adjoins house; and here, with the very stench of death rising through the boards, human beings sleep night after night, until the last sleep of all comes upon them years before its time.

The inhabitants themselves show in their faces the poisonous influence of the mephitic air they breathe. Either their skins are white, like parchment, telling of the impaired digestion, the languid circulation, and the coldness of the skin peculiar to persons suffering from chronic poisoning, or else their cheeks are flushed hectically, and their eyes are glassy, showing the wasting fever and general decline of the bodily functions.

And yet, as we stood doubting the fearful statement, we saw a little child, from one of the galleries opposite, lower a tin can with a rope to fill a large bucket that stood beside her. In each of the balconies that hung over the stream the self-same tub was to be seen in which the inhabitants put the mucky liquid to stand, so that they may, after it has rested for a day or two, skim the fluid from the solid particles of filth, pollution, and disease.

Tobin also quotes the archeological work done by Saxby and published in Current Archeaology 2012.12 The archeologists confirmed that deeper layers show a community that was once better off and ate a normal diet. The bones and waste of the layers in Dicken's era confirm what he and Mayhew reported. They subsisted on undesirable portions of meat - if any at all.

The Current Archeaology article12 also reports that the wooden beams used to support the galleries over the ditches were old and rotting at the time they were first used in Jacob's Island. The same was true of the wood lining the revetments of the ditch: decayed wood presumably salvaged from old ships. In its declining years, the infrastructure was patched together with rotted scraps of used wood.

This is pure conjecture on my part, but since the end of the Mayflower Ship is unknown, one might speculate that it was dissembled close to the shipyard from whence it sailed; and (perhaps) it's boards were used to prop up the sagging galleries of Jacob's Island. We will probably never know.

Those wishing to read more first hand accounts of life on Jacob's Island in the mid-1800's should check Tobin's article and his bibliography of resources.7

But Jacob's Island was more than just abject proverty: it was a swamp of criminals and villains. Andrew McIntyre describes Jacob's Island as a known "rookery" or criminal hide-out of thieves.8 Slums were frequently called "rookeries" in 19th century Britain, because of the tendency of rooks (or ravens) to make their abodes in such places in England's cities.

In an article dated 1917, H.W. Jackson describes the maze of criminal escape routes. "The structure of many of the old houses shows that they have been adapted for the concealment of crime. Subterranean connection between the houses, and windows opening on to the roofs of other dwellings bear witnes to its being a place where desperate characters found a hiding place, and where pursuit and detection was rendered next to impossible. Most of these dens have been pulled down since I have been on the district."10

It is in this maze of poverty and crime that Chapter 50 of Oliver Twist opens.

Bill Sikes House at Jacob's Island

Dickens did more than tell a story. He opened a nation's eyes to the destitution of a community in the midst of the capital, shielded from view by warehouses along the riverfront that poisoned it. The people of Britain read it and took notice.

In fact, so descriptive was Dickens, that many felt the exact house could be pointed at when they read these words:

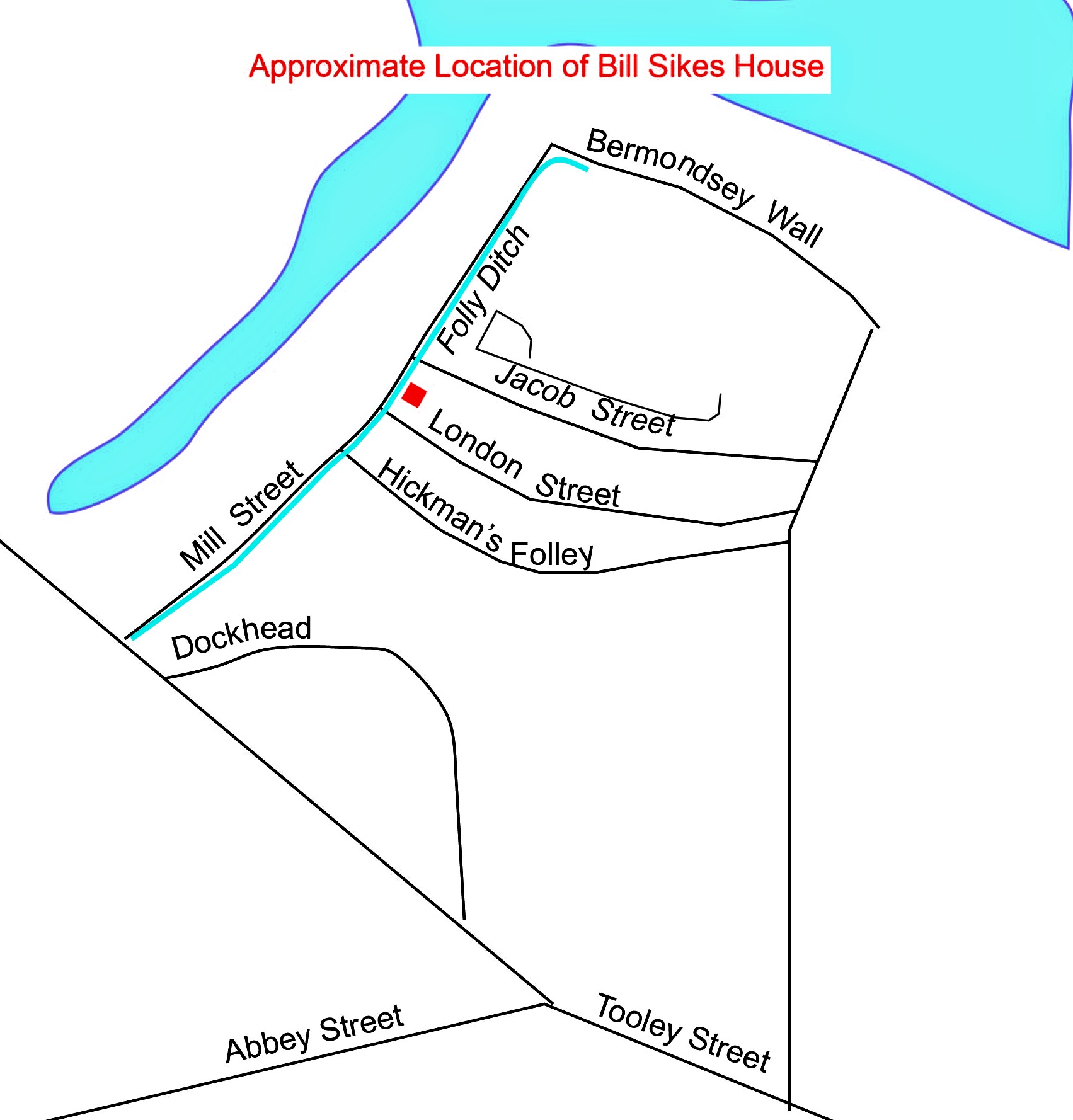

In an upper room of one of these houses -- a detached house of fair size, ruinous in other respects, but strongly defended at door and window: of which house the back commanded the ditch in manner already described -- there were assembled three men...

Before the bombs fell from the Luftwaffe, a house matching that exact description was identified. It was named "The Bill Sikes House." (Just to be clear, Sikes didn't own it, he didn't even live there. Toby Crackit lived there, but according to Dickens "The houses have no owners; they are broken open, and entered upon by those who have the courage, and there they live, and there they die." While Sikes didn't live there, he certainly died there; as much as a fictitious character can die.)

A 1925 newspaper articles places the exact house named as "Bill Sikes House" at 18 Edward Street.10 Edward Street is no longer there, but it ran North to South between Jacob St and Wolsely St (Hickman's Folly) and was just east of Mill Street.

The article states that in 1855, the actual house intended by Dickens was identified. Apparently, that particular house was a known criminal hide-away. Dickens was said to have visited the places where he placed his fictitious characters in order to develop more accurate settings. What are the chances that the contemporary criminals of that joint ever read his book?

What's Left

The search for Jacob's Island has taken us on a long journey: an ancient monestary, the gallows of pirates, a diverted stream and an old mill.An idyllic community became a thriving center of commerce and industry before plunging into poverty so abominable it defies elucidation. It cannot be visited; all traces have dissipated. All that is left is a plaque that marks that site of the medieval abbey and a museum named "Jacob's Island Gallery." In spite of its name, the gallery is located on the west of St. Saviour's Dock whereas the island of old was on the east of the dock.

There's really nothing left. Except, if one looks at aerial photographs and maps and compares it to the maps of old, a geographic resemblance can be discerned in the streets. And hidden beneath the ground, invisible to the eye, the Neckinger River continues to flow, unimpeded by sluice gates that once used its water to run its mill. Nothing else is left.

But before flames and builders and bombs could extinguish all traces of its existence, Charles Dickens penned a few paragraphs that allowed Jacob's Island to live forever.

Oliver Twist Unit Study

- Background Information

- Literary Analysis

- Reading Comprehension Questions

- Vocabulary Lists

- Hands-On Teaching Activities

- Maps

- Readers' Help Sections

- Model Sentences

- Writer's Challenges

- And More

Charles Dickens Description of Jacob's Island

Charles Dicken's exact words are provided below. The words that give clues to the location of Bill Sikes house are bolded. I can't confirm that those who located the house were correct, but there are enough specific clues to make it possible.Near to that part of the Thames on which the church at Rotherhithe abuts, where the buildings on the banks are dirtiest and the vessels on the river blackest with the dust of colliers and the smoke of close-built low-roofed houses, there exists the filthiest, the strangest, the most extraordinary of the many localities that are hidden in London, wholly unknown, even by name, to the great mass of its inhabitants.

To reach this place, the visitor has to penetrate through a maze of close, narrow, and muddy streets, thronged by the roughest and poorest of waterside people, and devoted to the traffic they may be supposed to occasion. The cheapest and least delicate provisions are heaped in the shops; the coarsest and commonest articles of wearing apparel dangle at the salesman's door, and stream from the house-parapet and windows. Jostling with unemployed labourers of the lowest class, ballast-heavers, coal-whippers, brazen women, ragged children, and the raff and refuse of the river, he makes his way with difficulty along, assailed by offensive sights and smells from the narrow alleys which branch off on the right and left, and deafened by the clash of ponderous waggons that bear great piles of merchandise from the stacks of warehouses that rise from every corner. Arriving, at length, in streets remoter and less-frequented than those through which he has passed, he walks beneath tottering house-fronts projecting over the pavement, dismantled walls that seem to totter as he passes, chimneys half crushed half hesitating to fall, windows guarded by rusty iron bars that time and dirt have almost eaten away, every imaginable sign of desolation and neglect.

In such a neighborhood, beyond Dockhead in the Borough of Southwark, stands Jacob's Island, surrounded by a muddy ditch, six or eight feet deep and fifteen or twenty wide when the tide is in, once called Mill Pond, but known in the days of this story as Folly Ditch. It is a creek or inlet from the Thames, and can always be filled at high water by opening the sluices at the Lead Mills from which it took its old name. At such times, a stranger, looking from one of the wooden bridges thrown across it at Mill Lane, will see the inhabitants of the houses on either side lowering from their back doors and windows, buckets, pails, domestic utensils of all kinds, in which to haul the water up; and when his eye is turned from these operations to the houses themselves, his utmost astonishment will be excited by the scene before him. Crazy wooden galleries common to the backs of half a dozen houses, with holes from which to look upon the slime beneath; windows, broken and patched, with poles thrust out, on which to dry the linen that is never there; rooms so small, so filthy, so confined, that the air would seem too tainted even for the dirt and squalor which they shelter; wooden chambers thrusting themselves out above the mud, and threatening to fall into it — as some have done; dirt-besmeared walls and decaying foundations; every repulsive lineament of poverty, every loathsome indication of filth, rot, and garbage; all these ornament the banks of Folly Ditch.

In Jacob's Island, the warehouses are roofless and empty; the walls are crumbling down; the windows are windows no more; the doors are falling into the streets; the chimneys are blackened, but they yield no smoke. Thirty or forty years ago, before losses and chancery suits came upon it, it was a thriving place; but now it is a desolate island indeed. The houses have no owners; they are broken open, and entered upon by those who have the courage; and there they live, and there they die. They must have powerful motives for a secret residence, or be reduced to a destitute condition indeed, who seek a refuge in Jacob's Island.

In an upper room of one of these houses — a detached house of fair size, ruinous in other respects, but strongly defended at door and window: of which house the back commanded the ditch in manner already described — there were assembled three men, who, regarding each other every now and then with looks expressive of perplexity and expectation, sat for some time in profound and gloomy silence.

SOURCES

Note: Because links change frequently on the web, and dead links mess up a page, the links below are not live. You can copy and paste them into your brower to get to the pages used in researching this subject.1. London Remembers - Bermondsey Abbey

https://www.londonremembers.com/memorials/bermondsey-abbey

2. River Neckinger Wikipedia

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/River_Neckinger

3. BlackCabLondon - Secrets of the Viaducts: Walking the London Bridge to Greenwich:

https://blackcablondon.net/2013/06/21/secrets-of-the-viaducts-walking-the-london-bridge-to-greenwich-arches-part-two/

4. Mayflower Pub

https://www.mayflowerpub.co.uk

5. Somerville, H - Jacob's Island

https://www.hsomerville.com/meccano/Articles/JacobsIsland.htm

6. Exploring Southwark - Great Fire of Tooley Street

http://www.exploringsouthwark.co.uk/great-fire-of-tooley-street/4588284787

7. Tobin, Robin - Finding Dicken's Jacob's Island: London Through the Eyes of Oliver Twist

https://m.facebook.com/notes/robert-tobin-tutoring/finding-dickens-jacobs-island-london-through-the-eyes-of-oliver-twist/471568526223140/

8. Mayhew, Henry - 1849 A Visit to the Cholera Districts of Bermondsey

http://members.tripod.com/philip_neal/mayhew.htm

9. McIntyre, Andrew - "Oliver Twist and Jacob's Island"

http://copperfieldreview.com/?p=377

10. Jackson, H.W. - Jacob's Island

http://members.tripod.com/philip_neal/jacobs_island_jackson.htm

11. Identification of Bill Sike's House: 1925 Article

NLA https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/90503069

12. Saxby, David - Digging Jacob's Island

https://www.archaeology.co.uk/articles/news/digging-jacobs-island.htm

13. Dickens, Charles - Oliver Twist, Chapter 50, first paragraphs